- The U.S. economy came to a sudden stop a year ago as Covid-19 became a pandemic.

- Getting the $20 trillion machine up and running again has been difficult, but progress has been made.

- A gauge from Jefferies measuring the current status has the economy running at 85% of its pre-pandemic self.

- While economists are generally optimistic about the recovery, they remain concerned about a daunting unemployment problem focused on the services industry.

- Declining coronavirus cases and easing of restrictions are providing the most hope.

Shutting down a $20 trillion economy in full swing seemed a daunting enough task by itself. Restarting that massive machine has proven still tougher.

A year ago, the government brought activity to a near-standstill in hopes of stunting the growth of what then was a largely unknown nemesis, a virus that spawned into a deadly pandemic whose breadth and depth was, at that time, impossible to measure.

All activity deemed nonessential stopped.

We're making it easier for you to find stories that matter with our new newsletter — The 4Front. Sign up here and get news that is important for you to your inbox.

No more restaurants or bars. No more concerts or theater. No big crowds – and no small crowds, either, for that matter. Thousands of small businesses had to close their doors while big-box retailers took in those customers. Through most of March and April those conditions persisted as Covid-19 cut a deadly swath across America.

Then, the restart.

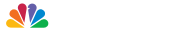

The U.S. gingerly reopened in May and then accelerated through the summer. A staggering 31.4% drop in gross domestic product for the first quarter turned into a 33.4% boomerang for the July-through-September period. Both numbers were unprecedented in post-Great Depression America.

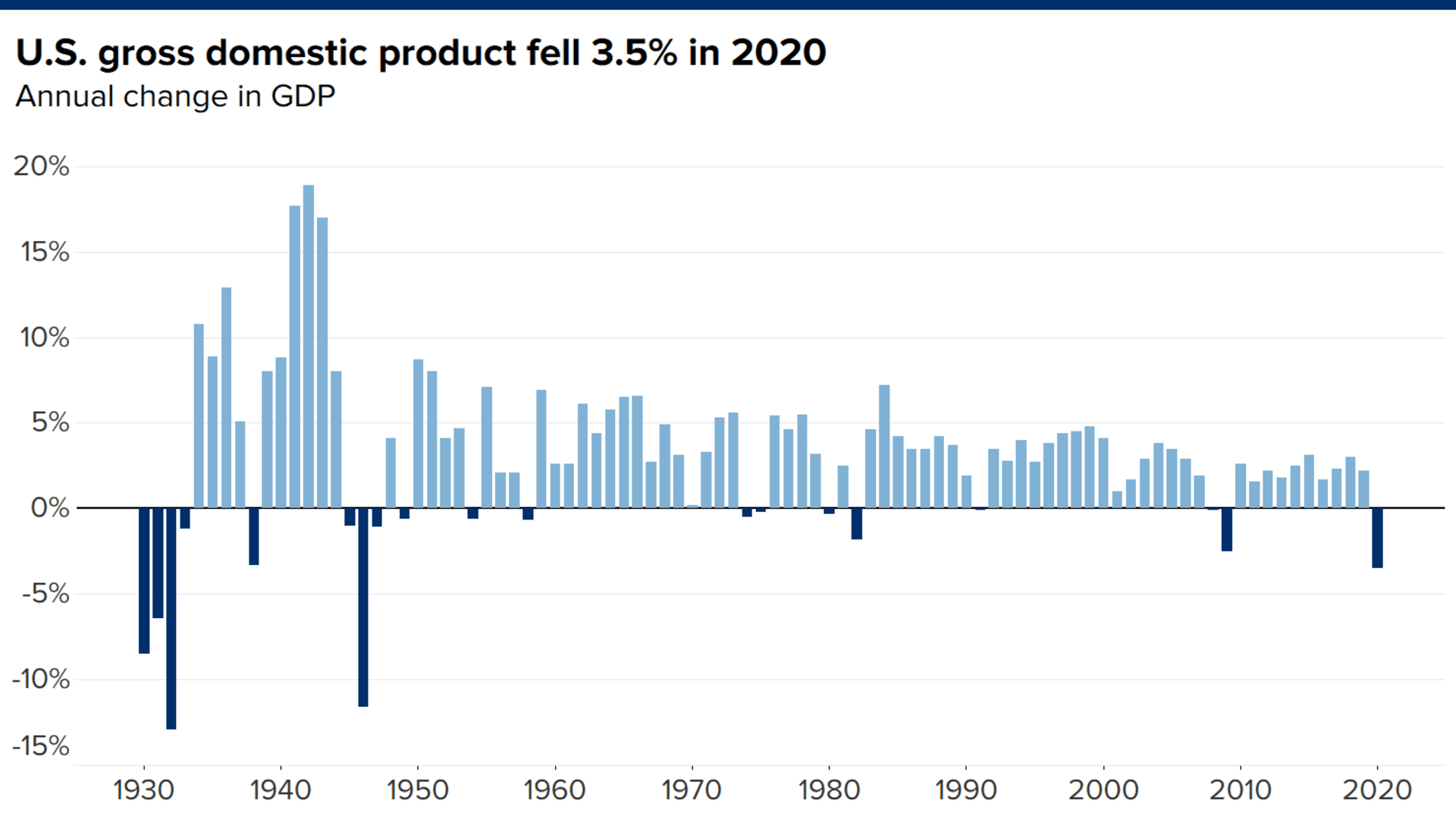

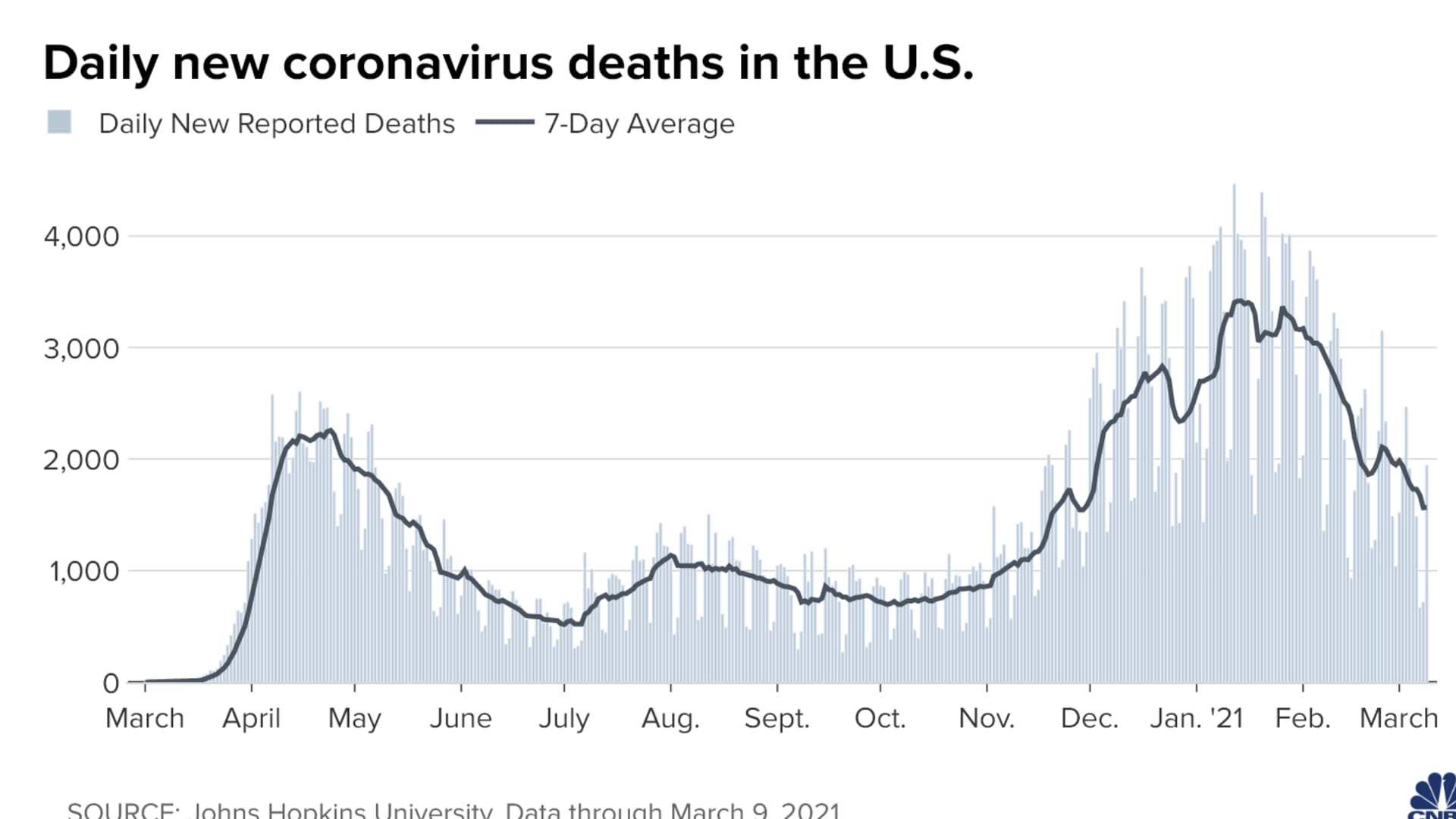

But as summer turned to fall, the virus came back with a vengeance and activity ebbed into the end of the tumultuous 2020.

Money Report

So now as the one-year anniversary comes Thursday of the pandemic declaration by the World Health Organization, the big question on many minds comes down to a familiar refrain: Are we there yet?

The answer: Not yet, but we're getting close.

"The recovery so far has been pretty impressive, actually," said James McCann, senior economist at Aberdeen Standard Investments. "There's obviously a good ways to go yet. In those parts of the economy that are still suffering from Covid distortions, we're still seeing activity depressed."

"We're increasingly very optimistic about the ability of the economy to recover quite robustly from here," McCann added.

One answer to the question of how close comes from Jefferies, which compiles a weekly gauge of where the economy is compared to pre-Covid levels. The firm uses high-frequency data indicators that measure things like retail foot and web traffic, job listings, restaurant bookings, flight activity, traffic congestion, mortgage applications and industrial production in a socially distanced mask-wearing world.

As of this week, the economy was at 85% of where it was a year ago. While that sounds pretty good by itself, the better news is that with Covid cases increasing at their slowest pace of the pandemic and vaccines now registering about 2.2 million a day, things are only going to get better.

"We're going to increase significantly from here," said Aneta Markowska, chief financial economist at Jefferies. "The momentum is good and it will get even better as you move into the spring months."

The shape of the recovery

Indeed, early-year growth that was expected to be lackluster or non-existent now looks powerful. The Atlanta Fed's GDPNow tracker, which uses incoming data to project quarterly growth, now indicates a gain of 8.4% in Q1, down from a high of 10% a week or so ago but still degrees above expectations just a few months ago.

If that proves accurate, it will be the fastest quarterly growth rate in the U.S. since Q4 of 1984, not counting the aberration of last year's third quarter.

Economists spent a good deal of time in 2020 pondering the shape of the recovery. The answer ranged from extreme optimism to a little quirky – a Nike "swoosh"-shaped theory was popular for a while – to the pessimism that the comeback would take a long time and result in a further widening of wealth inequality.

In the end, the two most popular conclusions were the "V" with its rapid rebound and the "K," and its implications of a two-speed recovery that left many parts of society behind.

The reality is that both had some validity.

An economy growing at what should easily be a 6%-7% pace for the full year and set to be back to pre-pandemic strength by the summer certainly qualifies as a V. But the imbalances toward those at the lower end of the spectrum, particularly those who once held jobs in the hospitality and leisure sector, suggests a K, though the bottom part of the letter probably should be drawn shorter than the top in such an otherwise aggressive rebound.

"We're still at the mercy of the virus, so it's still a bifurcated economy," said Liz Ann Sonders, chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab. "If you are not an asset owner, you are clearly on the losing end of the spectrum. That divergence could stay enormously wide."

If that narrative about asset prices and inequality sounds familiar, it should. It's a repeat of what happened following the financial crisis of 2008, when public policy skewed toward boosting stocks and corporate bonds and did little to help working-class folks who didn't have big equity portfolios to pad.

The financial crisis was followed by the longest bull market in Wall Street history; this time around, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has catapulted more than 70% after a brief March 2020 plunge that was met by a volley of Federal Reserve interventions, including a program in which it bought bonds from some of the biggest companies in the U.S.

This time, though, has been different even with the stock market resurgence.

Raining cash

Whereas policy help during the financial crisis came mostly from the Fed and its steep interest rate cuts and asset purchases, this time Congress chipped in with two monumental stimulus bills totaling more than $3 trillion. Fiscal aid included payments sent directly to millions of consumers — $1,200 in April, and another $600 in December and January.

Those cash infusions, temporary though they were, helped spur two hot rounds of consumer spending as well as a major uptick in the savings rate. At the same time, lending initiatives, most prominently the Paycheck Protection Program, helped keep some small businesses afloat and partially reversed the layoff stampede in the early days of the pandemic that saw 22.4 million American sent to the unemployment line.

The Fed also has had its foot on the gas. Early in the crisis, the central bank slashed its benchmark short-term borrowing rate to near zero and implemented a slew of lending and liquidity programs that were even more ambitious than what it did during the financial crisis.

Amid all the help, large pockets of the economy have recovered and done so strongly.

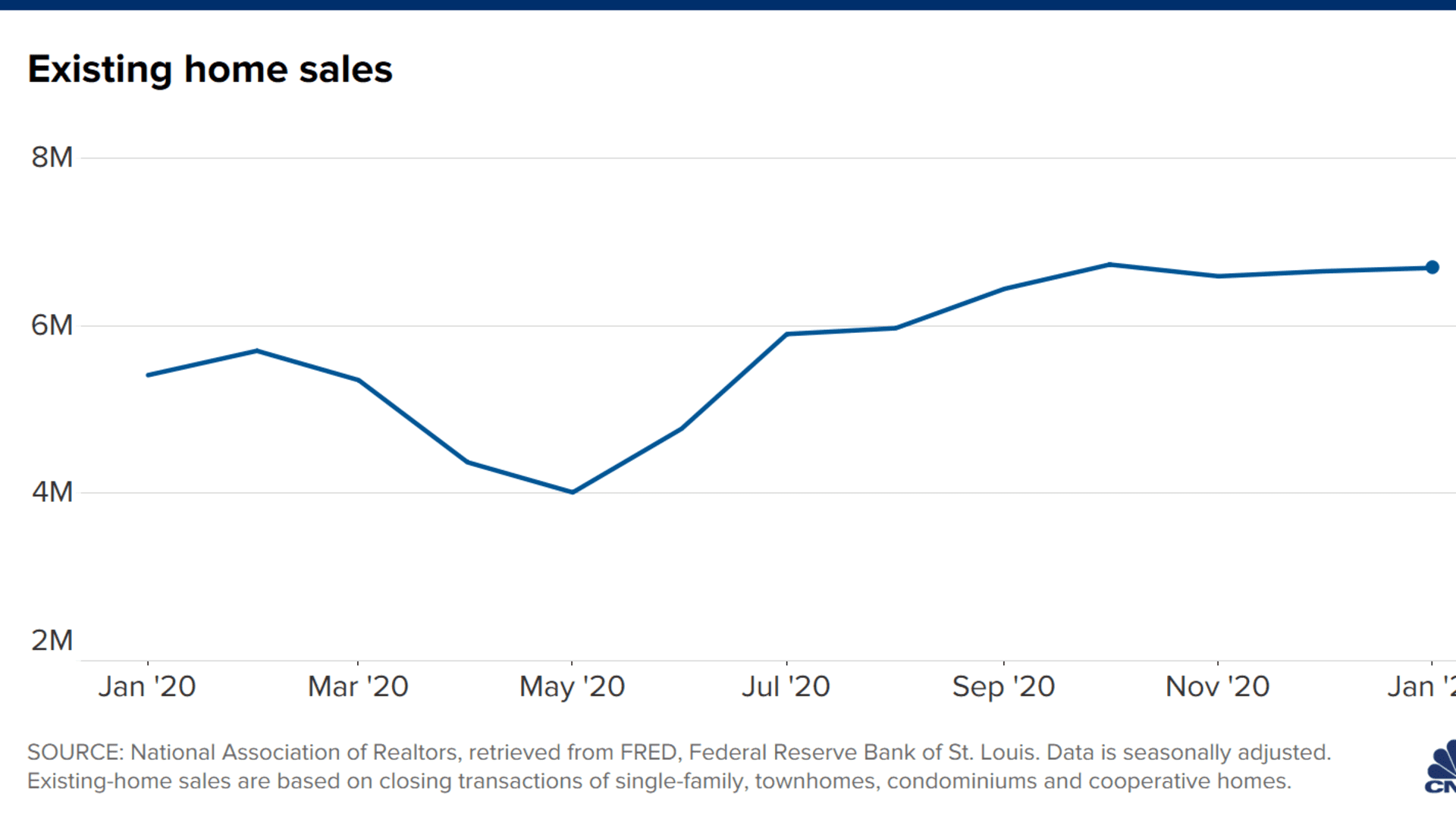

Real estate has been at a record pace for much of the pandemic period, with the median sales price of a home ending 5.4% higher at the end of 2020 from the beginning of the year as home sales rose 23.6%, according to the National Association of Realtors.

Retail also has thrived of late, with the more recent stimulus checks helping get the year off to a lightning start as sales jumped 5.3% in January. Manufacturing has been in a strong expansion as well and parts of the services economy are coming back.

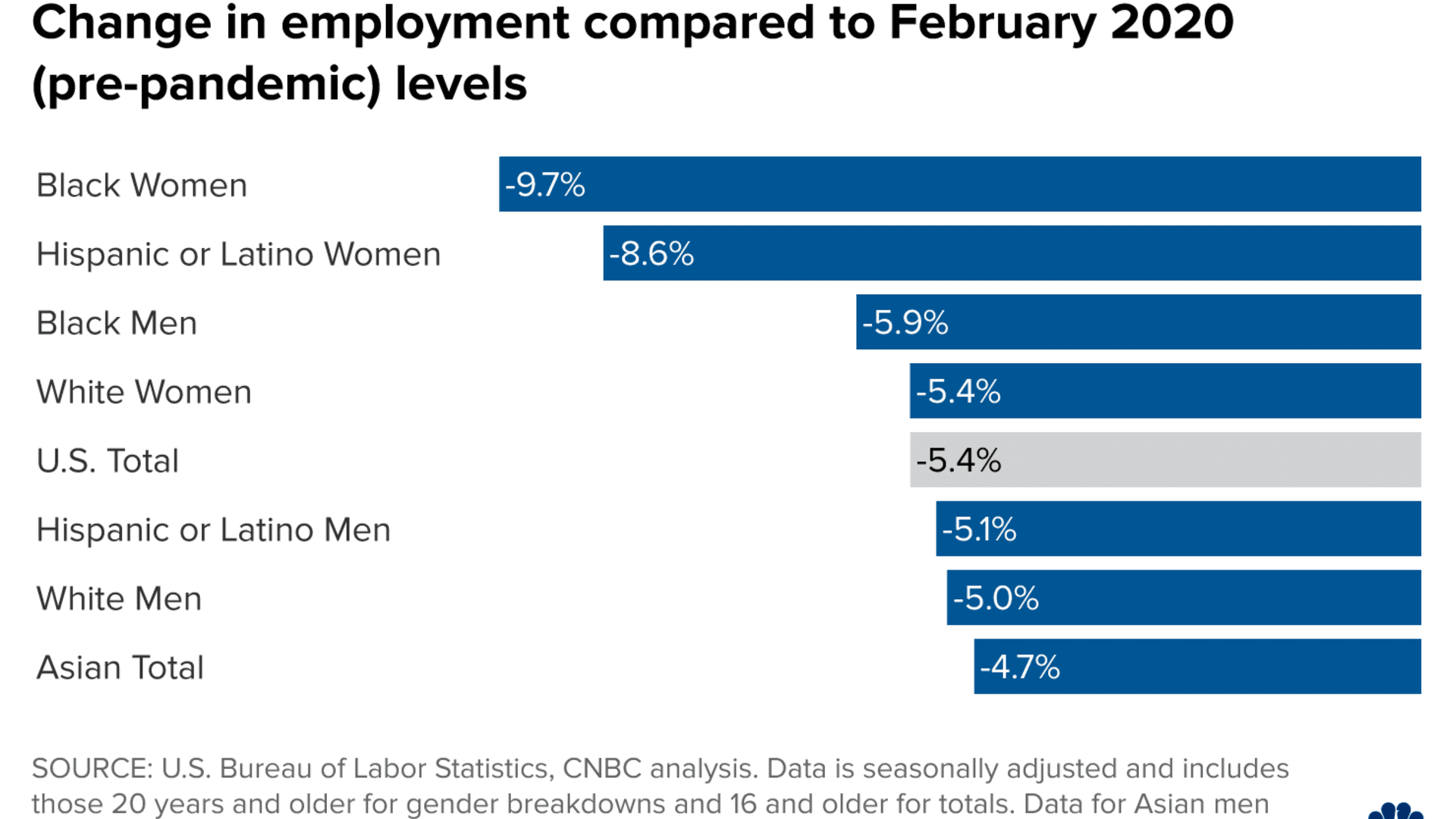

Still, neither the fiscal nor monetary help has been able to bridge the jobs gap. Doing that will be a matter of vanquishing the pandemic and lifting the restrictions that remain on businesses across the country. Those limits on activity have resulted in more than 8 million fewer Americans at work than a year ago.

"The lack of labor market dynamism is the single most critical issue in just the economy in general, especially in the United States," said Troy Ludtka, U.S. economist at Natixis. "This is the crucial question. How can you find a way to boost labor market demand? How can the government do that? That's a question where I don't think either political party really has any good answers."

Prior to the pandemic, unemployment had been at 3.5%, its lowest in more than 50 years, while GDP rose 2.2% in 2019 and 3% in 2018. The jobless rate zoomed to 14.7% at the height of the pandemic in April 2020 and most recently was a still-elevated 6.2%.

Washington politicians have tried to solve the jobs puzzle but to little avail. Another stimulus program set for adoption this week will arm consumers with more free money, but it won't help put sidelined workers back in their jobs.

While the virus prevalence has gone down markedly, most elected officials outside of Texas, Missouri and Florida along with a few other states are in no hurry to lift the most onerous restrictions on business activity. To be fair, that's in keeping with the thinking of many leading health professionals, but it still is crimping hiring.

Some hopeful signs emerged in February, when nonfarm payrolls expanded by 379,000, almost all of which came from hospitality. Still, that leaves about 3.5 million fewer workers in the business, an entire class that still needs public support to bridge the gap.

There were 6.6 million job openings in January, but still about 10 million workers to fill them. At the same time, the U.S. workforce has declined by 4.2 million from a year ago, suggesting a huge surplus of people waiting to go to back to jobs that may never be there again.

Neither V nor K

"We're not seeing huge upticks of folks entering the workforce just yet. We're kind of steady on the candidate side, while the job openings continue to rise," said Amy Glaser, senior vice president at national staffing firm Adecco. "We're anticipating by September jobs to be nearly back to a full recovery. The next six months are really critical, and we'll see gains every single month."

The best hope: A continued decline in Covid cases and rise in vaccines that will do far more than government transfer payments at this point.

"Most recently, the stimulus has come from the path of the virus. The numbers are falling meaningfully," said Michelle Meyer, U.S. economist at Bank of America. "That's allowed a lot of the restrictions in place to start easing."

Until the jobs market heals, however, the recovery, rather than be given a "V" or a "K," will instead get an "incomplete." There are still far too many variables at play to determine how strong or durable the recovery will be over the long run, and it won't be big-box retailers or trillion-dollar tech companies that will tell the tale.

Rather, it will be those still left behind who need to catch up.

Alfredo Ortiz is the president of Job Creators Network, a small business advocacy group that has, among other things, expressed its opposition to a Democratic congressional push for a $15 minimum wage. Ortiz thinks such measures will hammer small businesses at a time when they can least afford it.

Aside from that, though, he's helping push vaccine awareness and other efforts to halt the pandemic, believing that only after the restrictions are lifted will businesses and workers be able to recover fully.

"Obviously the vaccines are a huge help. We have a campaign going on that basically says help your local businesses get a short in the arm by getting one yourself," Ortiz said. "There's probably no better way of getting the economy back up and running."

He is encouraged by programs like the revival of the PPP small business effort, and knows that recovery is a race against time as much as anything else.

"Small business owners are hanging on by the tips of their fingers," Ortiz said. "We'll see if we caught them in time."