Maryland public school students have had some of the least opportunities in the nation to attend regular in-person instruction despite the state’s moderate COVID-19 spread.

Roughly half of normal in-person instruction is open in Maryland — the fifth-lowest in the nation as of April 13, according to Burbio, a community event tracker.

Maryland ranks toward the middle of states in daily average of new COVID-19 cases per 100,000 residents in the last seven days, at 23, according to the New York Times tracker.

We're making it easier for you to find stories that matter with our new newsletter — The 4Front. Sign up here and get news that is important for you to your inbox.

John Bailey, a visiting fellow at the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute — a Washington, D.C.-based think tank — produced a report in March analyzing the variety of studies around the world regarding COVID-19 spread and schools.

A common theme in these studies that the report details is that school reopenings, so long as they follow safety protocols, do not impact COVID-19 outbreaks in their surrounding communities.

“There’s a huge amount of learning from the past year that we haven’t adjusted it to the reopening of schools,” Bailey told Capital News Service. “We’ve not been grounding these decisions in evidence.”

Bailey emphasized the contrast between early concerns about COVID-19 and children to the resulting research over the past year.

While there were early concerns that children would be especially at risk to COVID-19 as they were to diseases like influenza, research has been clear that children, in terms of severity of symptoms, are at little to no risk of the coronavirus.

Another concern was that children would spread the virus by going to school regularly, but research has consistently shown that children spread the virus at a lesser rate than adults.

As of April 11, 59.4% of students in the country attend schools with a traditional everyday schedule, 28.4% attend schools with a hybrid schedule, and 12.2% attend schools that are virtual only, according to Burbio.

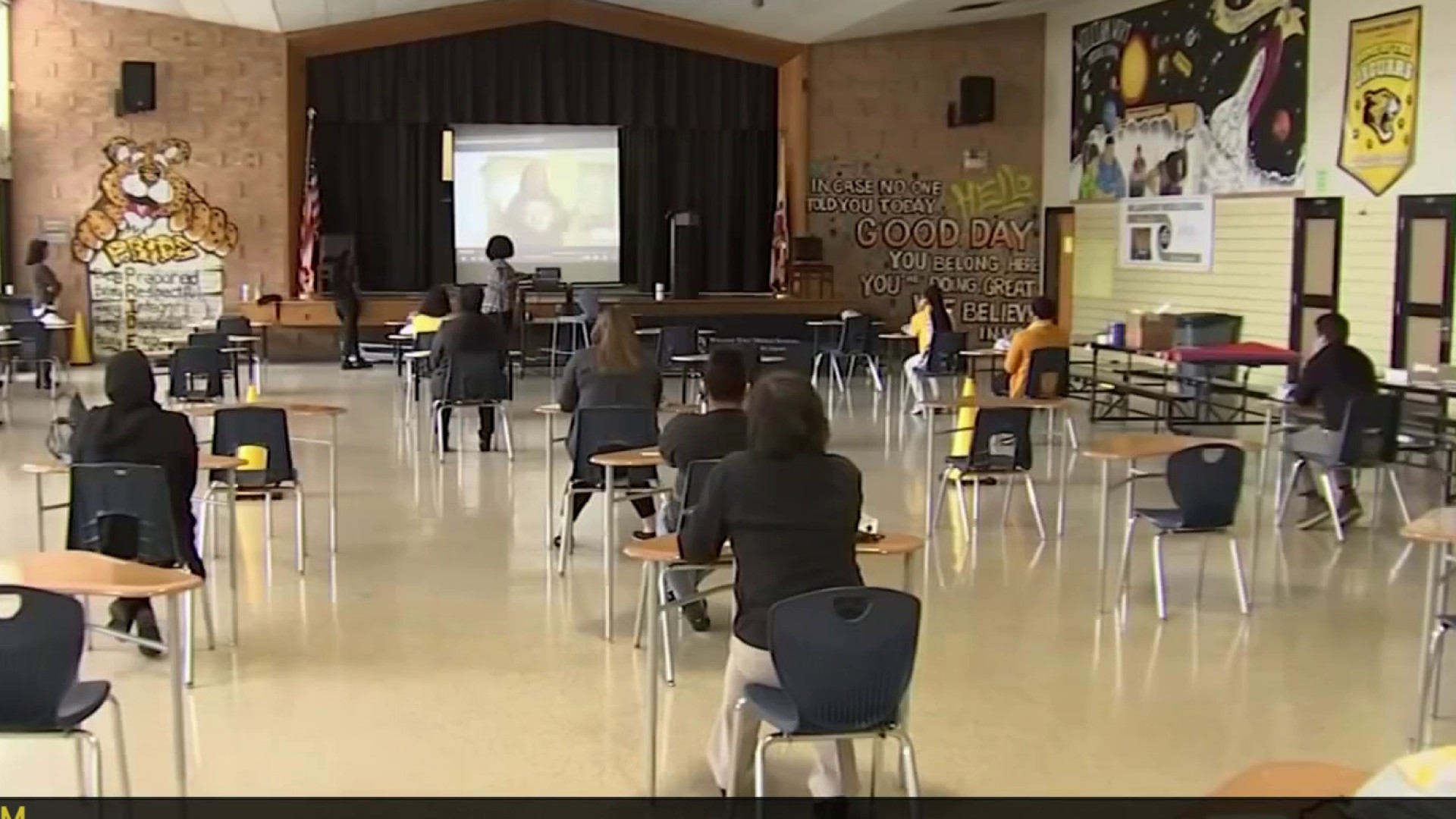

Monday marks the final phase of the reopening plan in Maryland, as six districts, including Baltimore County and Montgomery County, will be welcoming students for more regular in-person instruction.

While there is no public data on the amount of teachers vaccinated in Maryland, Cheryl Bost, president of the Maryland State Education Association, told CNS her union is getting fewer calls from members asking about vaccination appointments.

Bost said she’s heard some concerns from her members regarding lackadaisical enforcements of safety protocols and the quality of HVAC systems in aging school buildings.

Bost added that there could be more transparency at the state level in terms of detailing the number of COVID-19 cases in schools — a common theme nationwide.

The Maryland State Department of Education released data in March showing that in the second quarter of the school year (November 2020 to January 2021), jurisdictions with a middle school student failure rate of 20% in math and science increased by 800% in comparison to the previous year.

The data for high school students shows an 800% increase for math and a 300% increase for science. Increases in failure rates of English and social studies trended in similar directions.

When asked about the trend, Bost said that Maryland is not alone and that the comparison to a year with a pandemic is unfair.

“That’s disingenuous,” she told CNS. “How does your electric bill compare to other years? We’re home a lot more now.”

Bost did not express any concern that Maryland students could be falling further behind than states with more in-person instruction.

Bost instead pointed with optimism to the recently passed, multi-billion dollar annual education plan, Blueprint for Maryland’s Future, which is set to increase teacher pay, direct additional resources to poverty-stricken jurisdictions, and create new career training opportunities in schools.

“I’m excited about the opportunities moving forward with the Blueprint plan,” she told CNS. “There’s going to be so much more opportunity here in Maryland now.”

Bailey attributed the hesitancy of school reopenings in areas like Maryland in part to partisan fights and labor union conflicts.

“A lot of people have played into fear mongering,” Bailey told CNS. “We should have been celebrating these insights that we’ve been learning and highlighting these best practices.”

Looking ahead, Bailey said analyzing the impact of a lack of in-person instruction over the past year will focus on three main aspects.

The short-term effects, which he said are mostly being studied now, focus on the academic progress and mental health of students.

Then, he said, there’s the “medium term” — which regards college and career decisions.

In the long term, he said, shortcomings in these areas could lead to lost earnings and economic opportunity.

___

This article was provided to The Associated Press by the University of Maryland’s Capital News Service.