More than 32 years ago, a riot broke out in the Northwest D.C. neighborhood of Mount Pleasant after a Latino man was shot by a rookie D.C. police officer.

It was as if guerilla warfare had come to Mount Pleasant, a neighborhood described at one point as the most diverse in the District. But it was also a "powder keg," according to Sharon Pratt, the mayor at the time.

Many of those who participated in the riots — which came to be known as Los Disturbios de Mount Pleasant — had fled from civil wars, poverty and lack of education in Central America.

"Risking their lives to escape crushing poverty in their country only to continue being denied access to economic and social advancement in the U.S. was well beyond what many in the neighborhood were willing to bear," D.C.'s Latino Economic Development Center notes.

On the night of May 5, 1991, the streets filled with broken glass and charred vehicles as angry residents clashed with armor-clad cops.

From the ashes of the uprising came a renewed charge to improve the lives of Latinos in the District. But even today, there are hurdles the community has yet to clear.

This is the story of Los Disturbios de Mount Pleasant.

"It is perhaps the most consequential event in the history of Hispanics in Washington," José Suiero said.

Watch the full story:

May 5, 1991: '50 people saw 50 different things'

Los Disturbios de Mount Pleasant, as the riots came to be called, began on May 5, 1991, Cinco De Mayo.

Daniel Enrique Gómez, a dishwasher at Georgetown University, was among the revelers out drinking that day. He reportedly became belligerent in a restaurant.

Rookie D.C. police officer Angela Jewel, who is Black, was one of the two officers trying to handle the situation.

"And then it gets really murky. You had 50 people who saw 50 different things," American University professor Patrick Scallen said.

One man said the officer put one handcuff on Gómez before Gómez broke away from her, pushed her and pulled out a knife, according to NBC4 footage from 1991.

"He didn't have no weapon on him," someone else said. "And how could he get to the weapon if his hands were handcuffed?"

Jewel felt like her life was in danger, Scallen said.

According to a police spokesperson from that night: "What I can tell you is that about 7:30 this evening, we had an incident where a police officer on duty attempted to arrest three or four subjects in this area. When she attempted to handcuff one and place that person under arrest, the subject resisted. At that point, the subject produced what was believed to be a hunting knife, a fairly large knife."

Here's a montage of voices about what led up the shooting, and what people said they saw:

The officer shot Gómez once in the chest. He would survive, but that evening, the anger in the community began to build toward a boiling point.

"Chief Fulwood alerted me that we had an incident. I don't know everyone knew at the moment that it would escalate," former mayor Sharon Pratt said. "But understandably it did escalate. Because it was a powder keg already there."

As tensions rose around the scene of the shooting, Quique Avilés, today a poet and community activist, was five blocks away with a group of friends when one of them left to get more beer.

“He comes back, and 'Hey put the news on! Something's going on in Mount Pleasant.' And there it is, you know, cameras, and oh man, and the fight was already on.”

'The war in El Salvador came here'

But what was it that led up to that boiling point? How did this neighborhood erupt? To understand that is to understand the cultural makeup of Mount Pleasant in the early 1990s.

“Eramos invisibles," Abel Nuñez said. "We were invisible. And what you have to remember is that the incident that set off the riots was an act of violence between the police and the community."

The neighborhood’s history was shaped by the diaspora of Central Americans – mostly Salvadorans – fleeing a country marred by a civil war. That's where Quique Avilés grew up.

By the time the Salvadoran civil war broke out, there was already a pipeline established from El Salvador to Washington, D.C. And then there was an exodus.

"I mean, by the thousands,” said Avilés (pictured below). “And all of a sudden, D.C. is like, 'What? You know, who are these people? What are they doing here?' And the city was not prepared for for such change.”

The face of immigration to D.C. was changing rapidly. Previously, Latino immigrants in D.C. mostly came from the Caribbean, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Puerto Rico, said Latino community leader Roland Roebuck.

“In the ‘80s, we have a different tonality of migrants," Roebuck said. "We have Salvadorans coming into the area with a different racial attitude, meaning that in their particular country, the presence of Afro Salvadorans is almost non-existent."

And many of the young people who arrived were traumatized from fleeing their war-torn countries. By the early and mid '80s, homelessness and mental health issues were rising, said Lori Kaplan, former CEO of the Latin American Youth Center.

Many of these new migrants settled in Mount Pleasant.

"So by the time we get to the time of the riots, the uprisings, it's a very multicultural neighborhood," Scallen said. It was probably the most diverse neighborhood in D.C. at the time, he said: about 35% white; 25% to 30% Black, and 35% to 40% Latino.

The environment was "very divisive," recalled Abel Nuñez, who is now the executive director for the Central American Resource Center. "I mean, like the most segregated place for me growing up was the lunchroom at my high school."

Sharon Pratt, then known as Sharon Pratt Dixon, was the mayor of Washington, D.C. at the time.

“There was a growing sense of tension," she said. "The white community has dominated the culture of decision making of Washington, D.C. The Black community, for the first time, was feeling that, you know, we were on a path to have some empowerment."

For once, Pratt said, Black voices were being expressed. But with a significant influx of people from Central America, particularly El Salvador, there was a new clash of cultures.

As Quique Avilés noted, it was customary, especially in the heat of the tropics, for people to go outside and socialize under shade.

“After work, they talk; they play cards; they play checkers. And the cops did not like that.... These people started talking about loud music. People started talking about all kinds of stereotypes,” Avilés said.

There was also major tension with the police department, which didn’t have many Latino officers at the time. That created a disconnect with Latino residents, said Lt. Livio Rodriguez, special liaison branch director for D.C. police.

“The attitude of the police was, 'Hey, you here, you better speak English'," Roebuck said.

Cultural differences and lived history also came into play with Latino residents’ perceptions of police.

“You have to understand that within the Salvadoran community and Central American migrants, their perception of policing is very different,” Roebuck said, “because in their particular country, the police many times play a very oppressive role.”

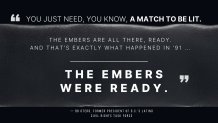

"You just need, you know, a match to be lit. The embers are all there, ready. And that's exactly what happened in '91, is that the embers were ready," said BB Otero, who — after the riots — would go on to become president of the Latino Civil Rights Task Force.

'Something's happening in Mount Pleasant'

"We get a call saying, there’s a revolt in Mount Pleasant," José Sueiro said in Spanish. "...There were two cops, who weren’t Hispanic and didn’t speak Spanish. Later we learned they had very little experience; they were rookies. ...First off, he was drunk. Secondly, they didn’t understand what he was saying. A group started to congregate and they [the police] got scared.”

As Quique Avilés summed up: “There were many versions. And this is before computers and cellphones. So the word just got out.”'

People started to gather, yelling and setting fire to trash cans.

"Mount Pleasant started to look like a bonfire all over the street," Sueiro said in Spanish. "They caught the city off-guard. This was a new population. Young people who weren’t integrated. Didn’t have jobs. Weren’t educated."

Scallen explained: "They'd take the flares from the glove compartment, open up the gas tank, light that flare, pop it down, boom. Never really seen that in D.C. before. That came straight from the streets of El Salvador. That came straight from the war. So the war in El Salvador came here.”

More than anything, Otero said, it was scary.

"And it was very distressing to see that it had come to that and that it takes a community uprising that way for people to pay attention," Otero said.

Pratt, the mayor at the time, said she received a lot of pushback, telling her she shouldn't go to the scene of the riots.

"But, you know, I had a sense that, you know, we had to reach out and try to bridge whatever tensions that might exist," she said.

The following day, the chaos continued, and the mayor declared a curfew.

As dusk began to fall on the second night, everyone was wondering what was going to happen. Would there be a repeat of the first night?

“The word was spreading," Quique Avilés said. "It's around 5 o’clock that second day. Man, there were all cameras, the priests and community leaders were out there with megaphones, and all of a sudden s**** just broke loose. And then the riot police, you heard it, pow pow pow pow pow, and their batons. And once they came to the Irving Street, Mount Pleasant and Irving, that's when they started firing the tear gas. And everybody started hurling all kinds of s***."

Avilés said he was among them.

"I was throwing bricks at the cops," he said. "I was helping reopen our apartments so that people could go and wash their faces."

The mayor ordered Metropolitan Police Chief Ike Fullwood to keep his officers from shooting.

“They could shoot tear gas, and those canisters did harm and wound people, but they could not shoot either rubber bullets or live bullets,” Scallen said.

No lives were lost.

"So the second night, it wasn't only a Latino uprising, it was a Latino and African-American uprising. And they looted stores," Suiero said.

The toll was felt keenly by shopkeepers “who often had sunk their entire life savings into these stores. Some of these were immigrant shopkeepers,” Scallen said. “They lost their life savings because their stores were unprotected, and the police did not physically bar looters from taking anything.”

"It helped, I guess, to wake up the leadership a little bit," Quique Avilés said, "about the necessity of the needs of a community that had come from a civil war."

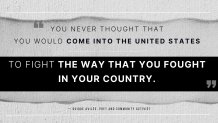

And the sights and sounds of the riots in Mount Pleasant brought old trauma to the surface for some.

“Because you never thought that you would come into the United States," Avilés said, "to fight the way that you fought in your country.”

The aftermath: more Latino officers and economic opportunities — but political power lags

"Riots are the voice of the unheard," Quique Avilés said. "And, uh, it's unfortunate that those things do happen in such violent ways. But at the same time, I think you come to a point when people's anger is just boiled over and there's something that says, ‘Uh uh, no more,' you know? No more."

By the third day, D.C. police amped up enforcement of the curfew, and most of the violence died down. But the spotlight on the Latino community was far from dimming.

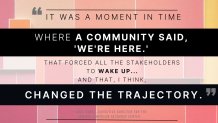

“It was a moment in time where a community said, ‘We're here.’ That forced all the stakeholders to wake up to the fact that there was a new community here and that it, I think, changed the trajectory," Nuñez said.

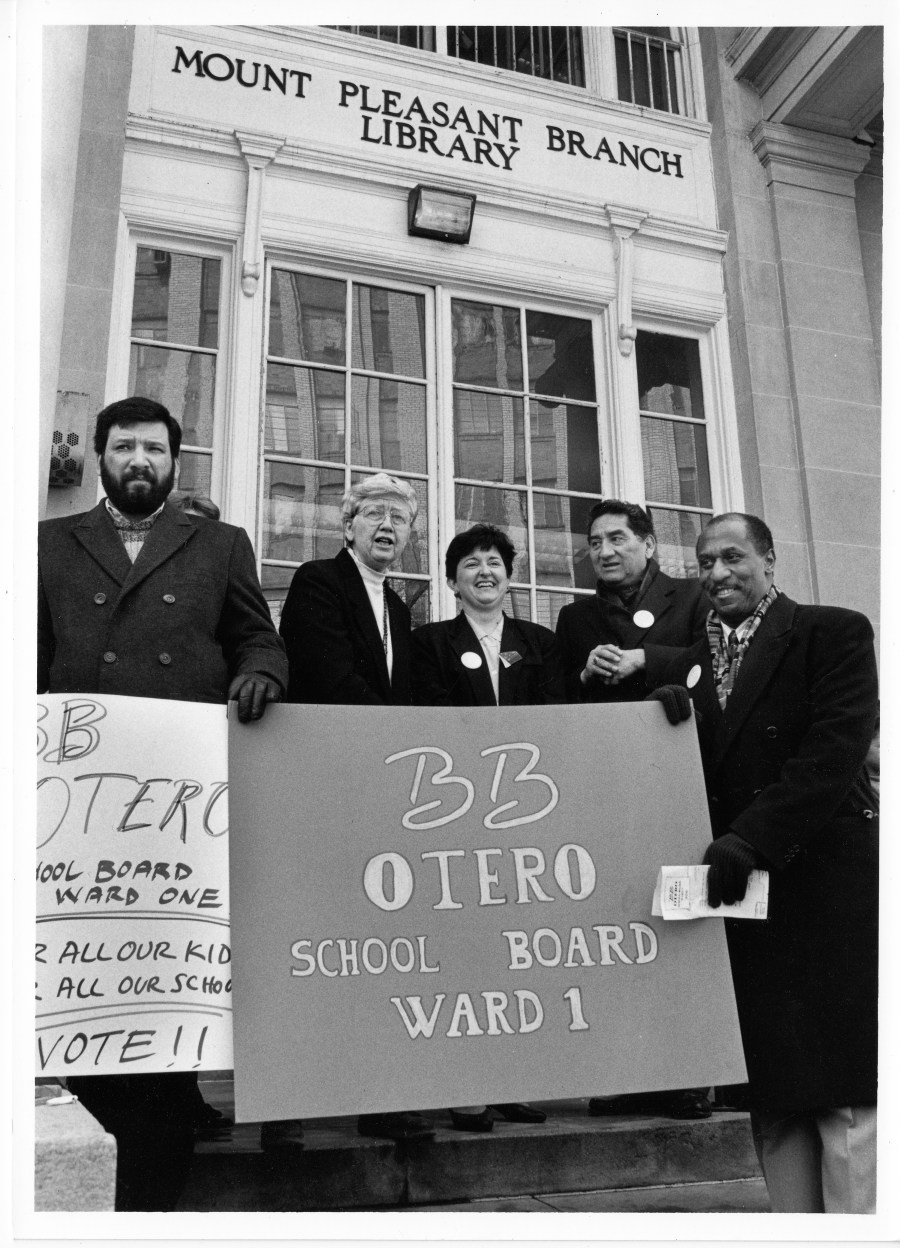

BB Otero (pictured above) and Pedro Avilés were among those in the Latino community who really pushed the D.C. government for change. They helped form the Latino Civil Rights Task Force in the wake of the riots.

The community then had an opportunity to engage with the mayor and establish communication channels that they didn't have previously, Pedro Avilés said.

“They wanted more resources to be allocated to Latino social services and other organizations," Scallen explained. "They said, ‘Look, we'd make up 10% of the city's population. We deserve 10% of the resources. We deserve 10% of city jobs."

The task force also successfully petitioned the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights to look into the root problems that Latinos were facing in D.C.

Two years after the riots, the commission issued a scathing 173-page report that condemned the treatment of Latinos in the District, and documented the systemic and institutional obstacles they faced.

The report stated:

“In calling for an investigation by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, the District's Latino community presented three main allegations to the Commission: first, that there existed a pattern or practice of abuse, harassment, and misconduct by the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department against the Latino community; second, that Hispanic representation in the District of Columbia government is not proportionate to the community's representation in the general population of the District of Columbia, and moreover, that the disproportionate representation was the result of discrimination by the District government; and third, that the Latino community was not receiving its fair share of government services. After examining these allegations, the Commission has found the allegations to have been justified.”

Pratt said: “With the impatience and the assertiveness coming from the Latino community that this incident triggered, I think we also had more of a constituency to move in a more positive, inclusive direction."

The District began hiring more bilingual police officers, providing more bilingual literature and established community centers in Mount Pleasant.

"Today, we have 400 Latino officers," Lt. Livio Rodriguez said. "We’re representing the Hispanic community more and we’re giving them resources and services. We’re telling them, we’re not the enemy, we’re your friend.”

Then came the Latino Economic Development Corporation, which helped Latino organizations get more contracts and grants.

“Would it have happened had the riots not happened? Probably much slower and with a much less coordinated kind of effort of demands and and focus around this,” Otero said.

But as the years went by, the momentum generated by Latino leadership began to stall, and many of the initiatives that they pushed for weren’t funded.

“The problem was that the bigger picture is that the city, Mayor [Pratt] Dixon, was still dealing with a massive budget deficit that had been left by the outgoing [Marion] Barry administration. Massive. Tens of millions of dollars,” Scallen said.

Despite that, Suiero said, "[T]he whole evolution of the way Latinos were seen by the city came naturally after that, because it was an invisible community and suddenly became very, very visible."

Since then, D.C. has had Latino ANC commissioners, a Latino school board member, and a Latino shadow representative.

"But in the political structure of Washington, D.C. — very few Latinos, very few," Suiero said.

B.B. Otero is one of the few Latinas to have held a high-level position in D.C. government, serving as the deputy mayor for Health and Human Services for four years.

It was a role she was thankful to have. However: “The reality is that it was really unfortunate that it was so late and so unique. Right? That …. we have no elected officials," Otero said. "And I ran for office once in 1992. But we have no elected officials. The District of Columbia has very few mechanisms by which people can grow politically.”

"Representation is critical," she said. “Representation is important. And it goes back to this issue of having folks who understand the communities that they're serving."

Today, Mount Pleasant looks a bit different than it did in 1991. Many of the folks who lived there in the '80s and '90s have been priced out. But more than three decades since the riots, life has improved for D.C.’s Latino community, and a lot of that change was borne out of three chaotic days in Mount Pleasant.

"Mount Pleasant has always been like this kind of little village," Quique Avilés said. "And I don't think there is any other place in D.C. that is like Mount Pleasant."