From complaints about unsafe shifts to an inability to provide adequate care, documents obtained by the News4 I-Team show the toll of the national nurse staffing crisis inside an area hospital.

The documents, obtained by the I-Team from a nursing union, lay bare how many nurses say they’ve struggled to care for their patients and themselves as their ranks fell during the pandemic.

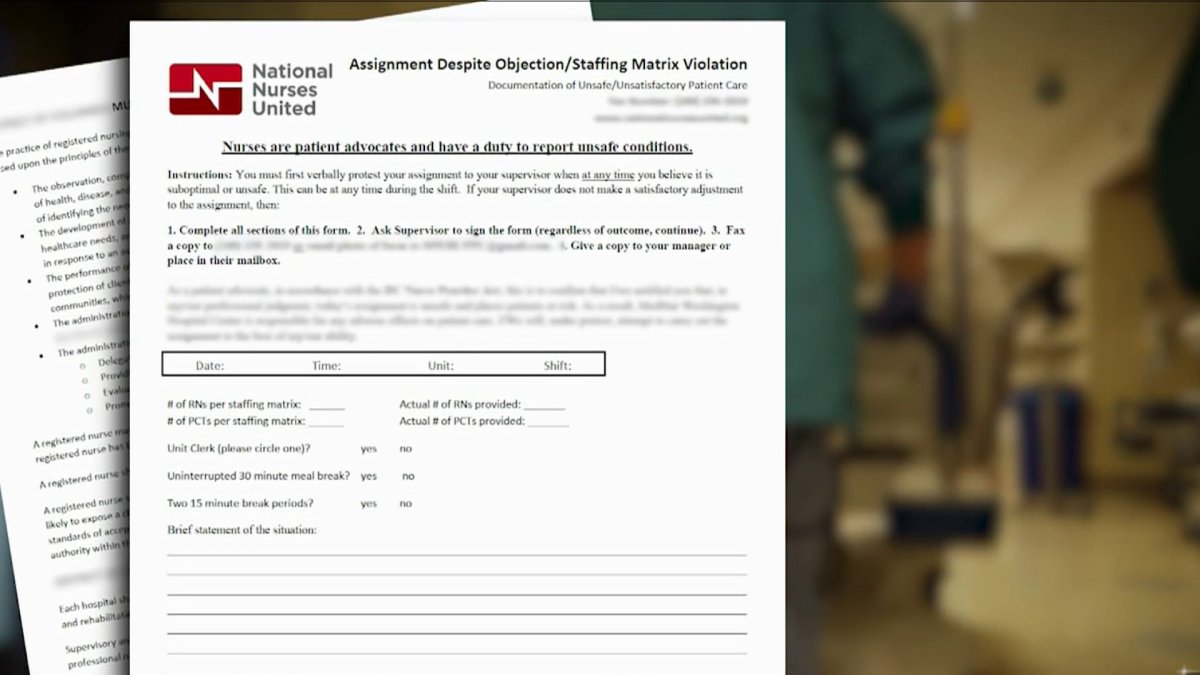

The I-Team reviewed nearly three years’ worth of complaints filed by unionized nurses in assignment despite objection (ADO) forms, which many unions use to document safety concerns on the job.

In one report, a nurse wrote, "Every nurse has an unsafe assignment. All but one RN has three babies, each with at least 1 ICU status.”

We're making it easier for you to find stories that matter with our new newsletter — The 4Front. Sign up here and get news that is important for you to your inbox.

In another, a person described five nurses managing five patients each, noting, “We can't provide adequate care.”

One nurse reported being left to manage six patients alone, calling the shift “grossly unbalanced” and “a safety risk to self and patients.”

The forms also show the lengths to which nurses have gone to help their peers and patients, documenting how one nurse worked 17 hours.

Local

Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia local news, events and information

The I-Team is not naming the hospital where these nurses work because News4 asked unions representing nurses at several hospitals for the forms, but only one provided them. Further, experts say the scenes depicted in the documents are just a snapshot of what’s happening across the country.

“A nurse's role is patient advocate, and when they're filling out one of these forms, they're doing it because they are worried about their patient,” said Jessica Brown, a union nurse familiar with the ADO reporting process.

An I-Team analysis of the union data shows nurses filed nearly three times as many of the ADO forms in 2022 as they did in 2020, with 79% citing “RN shortage" as a factor last year.

At the same time, data show the number of registered nurses at this hospital was steadily falling, from more than 2,000 at the start of 2021 to just above 1,700 last summer.

“When hospitals are not staffed appropriately, patients suffer,” Brown said.

Brown said the nurse staffing crisis, which worsened for hospitals across the country during the pandemic, is preventing nurses from delivering the standard of care patients need while also leading to burnout and driving many of her colleagues from the profession.

Asked if lives have been lost as a result of the staffing crisis, she paused before replying, “I think they have been. Yes.”

Experts say the pandemic exposed and then accelerated an already brewing staffing problem in the industry, with an aging boomer population driving increased demand.

The crisis was then worsened as nurses retired or left the industry, exhausted or demoralized by the COVID-19 crisis. Some of those who remained followed the lure of higher paying temporary travel nursing jobs, worsening the shortage in places they left behind.

Silver Spring, Maryland, resident Katie Sheketoff has felt the toll of the staffing shortage. The married mom of two was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2022 and suffered complications that landed her in the emergency room multiple times.

In one instance, Sheketoff said she needed an emergency blood transfusion and waited six hours for a bed. She said she later learned the hospital couldn’t locate a nurse who knew how to administer the transfusion through her mediport – something she said would’ve been far more comfortable than directly in her veins as they had shrunken during chemotherapy.

“It was incredibly painful. I was screaming. I mean, I've had two kids. It was as bad or worse than the worst of the labor pain,” she said.

While there, she said, a nurse confided her frustrations.

“She told me that they were so understaffed; she wasn't supposed to be there. She didn't have a background in ER nursing,” Sheketoff said, later adding: “It's a broken system, and the reality is that there just aren't enough nurses. They don't get the support that they need.”

According to a report on NBCNews.com, there were nearly 100,000 open registered nurse positions nationwide before the pandemic began. By September 2022, that number jumped to 203,000.

What’s more, a May 2022 report from the consulting firm McKinsey & Company predicts the U.S. could see a shortage of up to 450,000 registered nurses by 2025.

Deborah Burger, the president of the labor union National Nurses United, blamed hospital corporations for why so many nurses are dropping out of the profession, saying cost-cutting measures have cut too deeply into their ability to provide their standard of patient care.

“They're not willing to put their license on the line. They're not willing to cause harm to patients, so they remove themselves from the workforce,” she said.

She contends the country has enough qualified nurses to meet the demand, with data from the National Council of State Boards of Nursing showing more than 4.5 million registered nurses have active licenses as of March 1. But Burger said not enough are willing to work in hospitals.

"Hospital corporations have cut staff so badly that we just cannot humanly do it,” she said.

Like Brown, Burger also blamed the lack of widespread law mandating the minimum number of patients a nurse can care for at once. Her state, California, is the only one that has such a legal requirement.

“When we improved the staffing ratios in California, there was no longer a nursing shortage,” Burger said.

Those who have remained on the job are speaking out.

Last year, nurses at Howard University Hospital in D.C. held a one-day strike to demand better pay and more nurses. In January, 7,000 nurses walked off the job in New York, calling for increased staffing, too. And in February, nurses at George Washington University Hospital announced a push to unionize, citing a desire for “safer patient care” and “adequate staffing.”

Julian Walker, spokesman for the Virginia Hospital and Healthcare Association, said there’s no doubt the shortage “has an impact on how care is rendered.” But he said Virginia has managed to maintain good care.

"Outside observers who were evaluating patient safety, patient quality, clinical excellence in Virginia continue to rate the Virginia hospital community and Virginia hospitals as among the best in the nation,” he said.

But it hasn't been easy. He said his organization worked to bring retired nurses back to hospitals during the pandemic and is now behind a campaign called "On Board Virginia" to attract new healthcare workers to the commonwealth. As of now, the state has more than 11,000 job openings for healthcare workers, he said.

“We're trying to get to people at a young age; trying to appeal to them and say there are real values and benefits to careers in health care,” he said.

In statements, other hospital associations described their efforts to recruit and retain workers.

The Maryland Hospital Association said its members are raising nursing wages by 25% on average. The DC Hospital Association said it's working to recruit nurses through higher wages, referral and retention bonuses, as well as childcare and elder-care help.

The American Hospital Association said in a statement it’s urging Congress “to enact federal protections for health care workers against violence and intimidation, to invest in nursing schools, nursing faculty and hospital training time, and to reauthorize, expand, and fully fund nursing workforce development programs.”

News4 photographer Carlos Olazagasti contributed to this report.

CORRECTION (5:31 p.m., March 2, 2023): An earlier version of this story overstated the number of registered nurses with active licenses in the U.S.