Immigrants working on a remote Kansas ranch toil long days in a type of servitude to work off loans from the company for the cost of smuggling them into the country, according to five people who worked there.

There are no holidays, health insurance benefits or overtime pay at Fullmer Cattle Co., which raises calves for dairies in four states. The immigrants must buy their own safety gear such as goggles.

One worker spent eight months cleaning out calf pens, laying down cement and doing other construction work. Esteban Cornejo, a Mexican citizen who is in the U.S. illegally, left Kansas in November after paying off debt, which he figures was nearly $7,000.

The pay stub Cornejo shared with The Associated Press shows he worked 182.5 hours at $10 an hour over two weeks — an average of 15 hours a day with Sundays off. His pay was $1,828.34 before taxes. Also deducted was a $1,300 “cash advance repayment” that he said was a company loan for bringing him into the country.

His take-home pay was $207.46, the pay stub shows, or just over $1 an hour working at Fullmer Auto Co. Texas LLC, which does business as Fullmer Cattle.

“It is like slavery what they do to those poor people,” said Rachel Tovar, another former worker who spoke to The Associated Press.

Tovar said she was interviewed recently by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent, who asked about the company’s Kansas employment practices, but ICE declined to say if it is investigating.

U.S. & World

The day's top national and international news.

Dean Ryan, the company’s attorney, said in an email that the allegations “are simply not true.”

“There was no smuggler’s fee and has never been,” Ryan wrote, adding that there are “plenty of people willing to work in western Kansas without having to ‘import’ them.”

Ryan said company policy is to give pay advances to workers who have no credit. He said those loans are made so employees can purchase a vehicle or put a down payment on a home.

President Donald Trump’s administration has cracked down on immigrants living in the country illegally. But it has said less about the companies that employ them, let alone a company accused of using smugglers to bring workers to the United States.

The plight of the Kansas workers also highlights the exploitation that immigrants face when a company forces them to pay off debt with work, a practice called “debt peonage.”

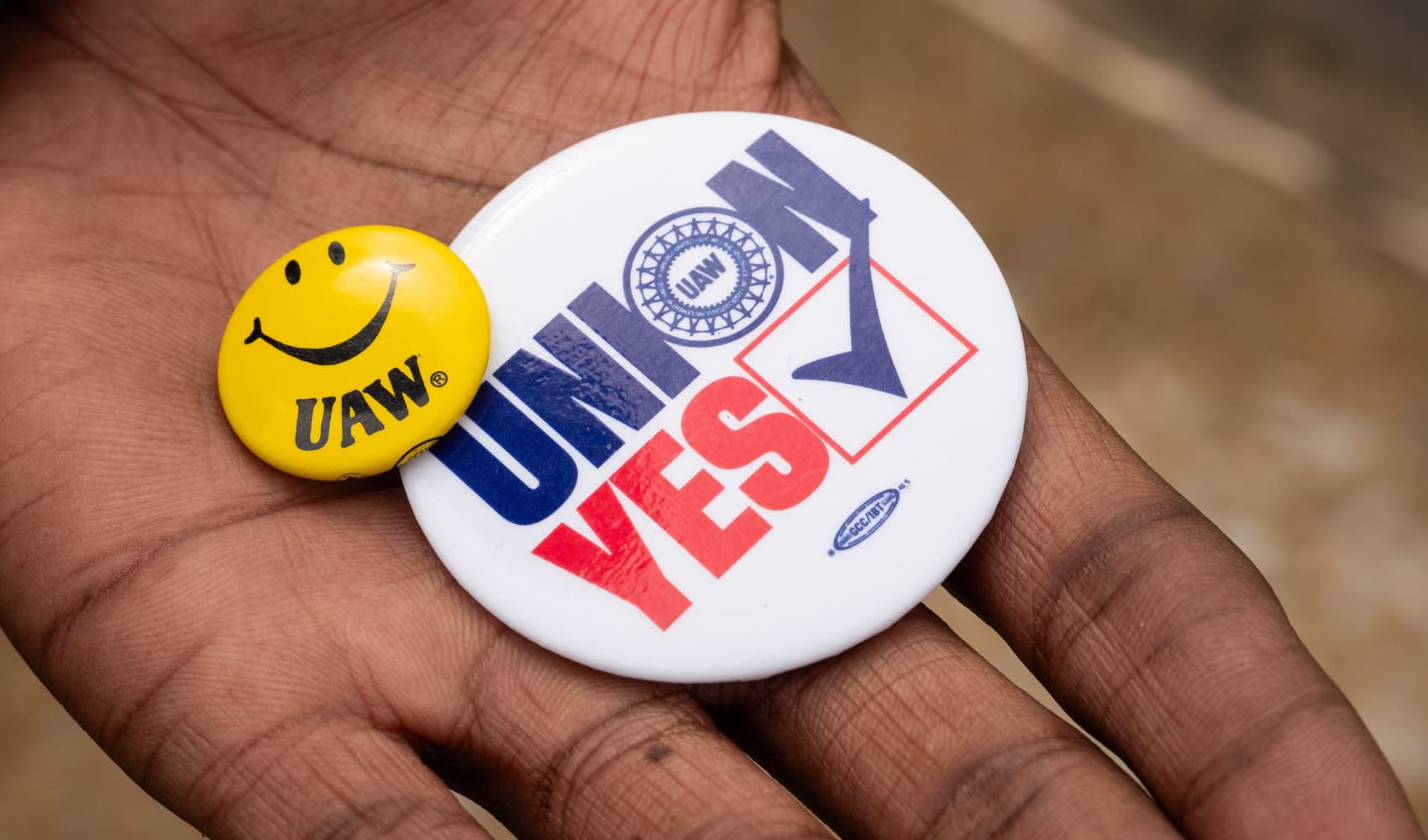

Under federal law, employers do not have to pay overtime to agricultural workers. Erik Nicholson, national vice president for the United Farm Workers union, said it is not unusual for employers to recruit immigrant farmworkers. Some employers use kickback schemes, although deducting from paychecks is “pretty brazen.”

Arturo Tovar is Rachel’s husband and a Mexican citizen who lived illegally in the U.S. and was a Fullmer manager for 11 years. He said the smuggling process worked like this: When the company needed workers, Arturo asked employees if they knew someone who wanted to work in the United States. The company gave him the phone number of the “coyote,” or smuggler, in Piedras Niegras, Mexico, to make the arrangements.

The company would give Arturo Tovar a check, which he would cash. A partial payment was made to the smuggler upfront and the rest when the immigrant reached San Antonio or Houston, where the immigrant would be picked up. If law enforcement asked questions about the cash, the employee was instructed to say it was for used cars the company bought at Texas auctions.

Rachel Tovar, a U.S.-born citizen, said that once the loan to bring an immigrant into the country was almost paid, the company often sold used vehicles to employees in what she believes was an effort to keep them in debt.

Arturo Tovar voluntarily left the country in lieu of deportation after pleading guilty last year to misdemeanor theft stemming from what the couple says was a false company accusation after he was hurt on the job. The company contends the Tovars have an agenda and lack credibility.

But another former employee told AP that Fullmer also loaned him money for the coyote to smuggle someone. AP is not naming the ex-worker out of concern for that person’s safety.

A fifth ex-worker confirmed the general accounts of those who allowed their names to be used but asked for anonymity because that person also has safety concerns.

Fullmer Cattle’s calf-feeding operation is outside of Syracuse, a farming community of 1,800 about 16 miles from the Colorado border. Former workers say some employees live in company-owned trailers at the ranch or a nearby property, for which the company deducts rent.

The company says it raises tens of thousands of Holstein calves for 18 dairies from Texas, Kansas, Colorado and South Dakota. Newborn calves are taken away from milk cows and sent to Fullmer to be bottle-raised and weaned. The heifers are sent back as milk cow replacements, while the bulls are sent to feedlots to be fattened for slaughter. Among the benefits Fullmer Cattle touts to customers on its website is “lower labor costs.”

The Kansas ranch offered owner Que Fullmer a fresh start following a 1998 immigration raid at his Chino, California, ranch where authorities found workers in what a California labor official described as “economic slavery.” The Kansas ranch also offered Fullmer a chance to rebuild after bankruptcies cost him the bulk of his operations in Muleshoe, Texas.

Fullmer pleaded guilty in 1999 in California federal court to a felony count of harboring and concealing immigrants in the country illegally. He was sentenced to six months of home detention, a $10,000 fine and ordered to perform 500 hours of community service, court records show.

In December, he was charged with illegally casting election ballots in both Colorado and Kansas in 2016. The registered Republican is accused of voting more than once and other violations. The case is pending in Kansas.

As a result of Fullmer’s past immigration-related conviction, the lawyer for the company said in an email that it takes “extra care” not to hire workers who are in the country illegally.

Associated Press researchers Jennifer Farrar and Rhonda Shafner in New York contributed to this report.