When she moved from Ohio to Virginia to fulfill a lifelong dream of working with horses, Andy Jane Armstrong didn’t think her future would depend on a cable-run ferry line established in the late 1700s.

Armstrong, 28, found a home in Leesburg about eight miles from the farm in Poolesville, Maryland, where she put her degree in equine teaching and training to use. Leesburg was more lively than Poolesville, she said, although her 20-minute commute over the Potomac River depended on White’s Ferry, which began shuttling travelers between Maryland and Virginia before George Washington was president.

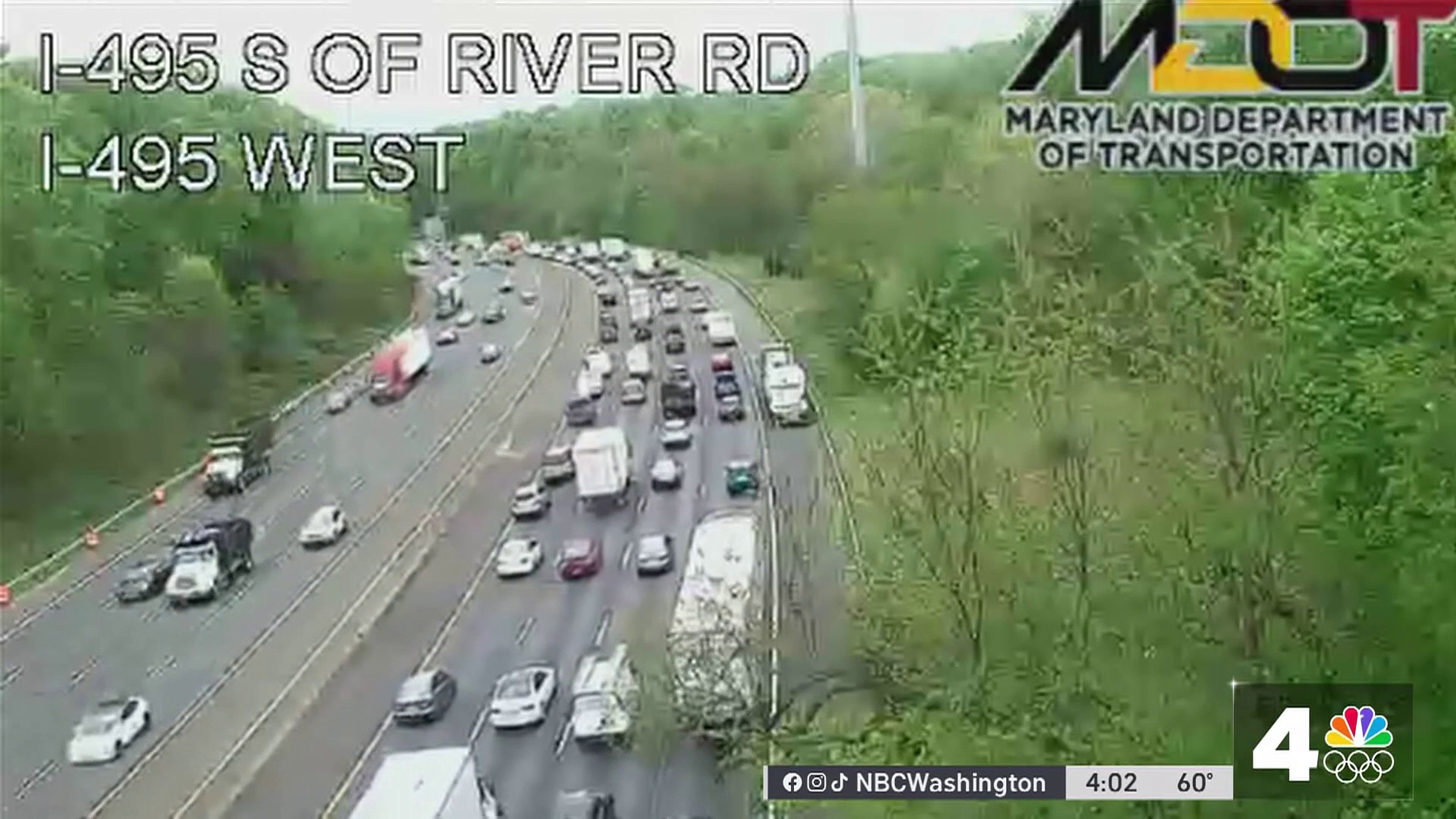

Then, on Dec. 28, 2020, White’s Ferry ceased operations — the victim of a long-running property dispute that, despite a change in ferry ownership and attempted intervention by two states, continues a year later. Overnight, Armstrong’s commute no longer included a 3-minute, 30-second ride across a river, but a 60-mile round-trip trek on exurban roads that adds two hours to her workday, if traffic is reasonable — and four hours if it’s not.

Skeptical that she can afford a home in Maryland, Armstrong is considering a career change that would eliminate the lengthy commute.

We're making it easier for you to find stories that matter with our new newsletter — The 4Front. Sign up here and get news that is important for you to your inbox.

“It’s definitely an adjustment,” she said. “I’m doing what I’ve grown up wanting to do my whole life.”

Armstrong is among hundreds of daily commuters feeling the effects a year after the ferry’s closure. As the ferry’s current and former owners spar with the family that owns the ferry landing, an agreement that could reopen the service has proven to be elusive.

A $200,000 study co-sponsored by Montgomery and Loudoun counties from October found that up to around 800 cars used the ferry daily, which cost $8 round-trip for vehicles. By 2040, according to the study, demand for trips could exceed 2,300.

Transportation

Reporter Adam Tuss and the News4 team are covering you down on the roads and in transit.

The study considered alternatives to simply restarting the service, including using dedicated queuing lanes and electronic prepayment systems — changes that could save travelers about $9 million by 2023 and about $13 million by 2040. However, the faster solution would be inspecting the ferry, hiring staff to run it and restringing the cable.

“If agreement regarding the Virginia side access issue is reached, service could potentially restart within weeks,” the study said.

Libby Devlin, a co-owner of Rockland Farm, said in an interview that the Virginia property used as a landing has been in her family since 1817. After the ferry service expanded the landing in 2004 — without her permission, Devlin says — years-long negotiations culminated in a lawsuit in 2009 followed by a ruling last year that White’s Ferry had trespassed. The farm was awarded more than $100,000 in damages.

After the ruling and subsequent ferry closure, Devlin said Rockland made a variety of offers, including buying the ferry, selling a permanent easement for $2 million, charging a 50-cent fee per vehicle, or entering binding arbitration to resolve the dispute. She said the offers were rebuffed.

“I don’t know why the ferry’s been closed this long,” she said. “The new owner is holding the ferry hostage. I believe our offers have been very reasonable and the ferry should have been opened long ago. And if he thinks they’re unreasonable, why not go into binding arbitration with us?”

Chuck Kuhn, chief executive of JK Moving Services, has conserved more than 4,000 acres in Loudoun and other Virginia counties, and he bought the ferry in February. Once the land dispute is settled, he said, the service could reopen within 30 days.

“We did not buy the ferry with the intention of getting rich,” he said. “We purchased the ferry because we did not want to see the ferry removed from the river and done away with forever.”

Kuhn said negotiations with Rockland are at an impasse after he offered to buy the farm for $13.5 million — more than its appraised value. He said he’s unwilling to pay $2 million for an easement or 50 cents per vehicle, because the “economics of what they’re proposing are unreasonable” and because Rockland wants the right to cancel the contract at any time.

Devlin said Kuhn offered to buy the farm before he bought the ferry, and the offer had since been rescinded. She also said cancellation rights were not a current contract term. “I find it hard to believe that the fare (which has not been raised in many years) is so inelastic that people would not pay an additional 50 cents,” she wrote in an email.

Kuhn also objected to characterizations of Rockland as a “struggling local farm,” pointing out that it’s partly owned by hedge fund manager Peter Brown, Devlin’s brother, while Devlin is a “very minority shareholder.” (Brown declined to comment.)

“I had no idea how difficult Peter Brown and his partners would be to negotiate with,” Kuhn said. “He’s a very experienced businessperson.”

Devlin said her brother is a “passive shareholder” — but the size of his stake is irrelevant, because the farm’s owners want “to keep it in the family.”

“I don’t know if (Kuhn is) fantasizing about other people’s money when I’m the one he dealt with,” she said. “I live here. I work here. I make the decisions.”

With Kuhn and Devlin unable to reach an agreement, former ferry owner Herbert O. Brown, whose family operated the ferry for decades, supported Kuhn in a Loudoun Times-Mirror opinion piece. He wrote that no owner could operate the ferry as a business based on Rockland’s demands, and that the landing “was considered public” for more than two centuries.

“I got rid of a headache, but I’m still involved as much as I can,” he said in an interview. “It was in the family for 75 years. … I hated to close it, but it just made no sense to go to work.”

Kuhn has advocated that Loudoun take the property through eminent domain, an option Devlin opposes. In a December newsletter, Loudoun County Board Chair Phyllis J. Randall (D-At Large) said the board is “not talking about eminent domain.” Loudoun County spokesman Glen Barbour said in an email that “there has been no further direction from the Board of Supervisors.”

“Board members reiterated that the parties involved should work together to find a solution that would result in the resumption of ferry services,” Barbour wrote. “The County remains hopeful that the ferry will operate again as the County has recognized the significance of the ferry to the region’s transportation network.”

As the ferry languishes, both sides of the crossing are struggling. Hannah Henn, the Montgomery County Department of Transportation’s deputy director for policy, said Poolesville was “harder hit from the closure of the ferry than from covid.”

“We are neutral on who is operating the ferry, but we are focused on the fact that reopening it is a key to our transportation efforts,” she said. “The legal hurdles are really all on the Virginia side.”

Eric Rose, who has run Bassett’s Restaurant in Poolesville for more than three years, said business is down 20 percent amid the pandemic and the ferry’s closure. Though the restaurant’s website says it’s “minutes from … historic (White’s) Ferry,” the hundreds of cars that used to stream by Bassett’s daily simply don’t these days.

Rose said he “thought this ferry issue would be done a while ago.”

“I think they both just need to come to the table,” he said. “Think about the communities this both affects and not just about money. There’s a lot of lives, families and businesses that are affected by this, and I think both sides need to come to an agreement.”

In the meantime, commuters such as Armstrong will continue to seek out alternative ways to cross the river. She’s not optimistic after months of failed negotiations, but she continues to hope for a breakthrough.

“I expect in six months we’ll still be in same place,” she said.