Head injuries - not concussions - cause chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative brain disease most commonly associated with NFL players, a new study says.

The study led by Boston University looked at the brains of four dead teenage athletes who had suffered head injuries days or weeks before they died. Two of the teenagers died by suicide.

One teen's brain showed early-stage CTE and two others had buildup of tau protein, an indicator of CTE found in athletes and soldiers who have suffered brain trauma. CTE progresses when tau protein accumulates and can cause dementia, mood swings, depression, suicidal thoughts, aggression, and other symptoms.

"It's kind of staggering to even think about this: A teenager with a neurogenerative disease," said Dr. Lee Goldstein, a co-author of the study and an associate professor for Boston University School of Medicine.

Also troubling is the short amount of time it took for signs of CTE to appear.

"We also saw the very earliest fingerprints of CTE soon after these injuries, and this is really very profoundly disturbing," Goldstein said. "What it tells us is as these hits are occurring even in the early aftermath — days, weeks, months after these injuries, this disease is already being kicked off."

Researchers took their work a step further and replicated repeated hits to the head and blast exposures with lab mice.

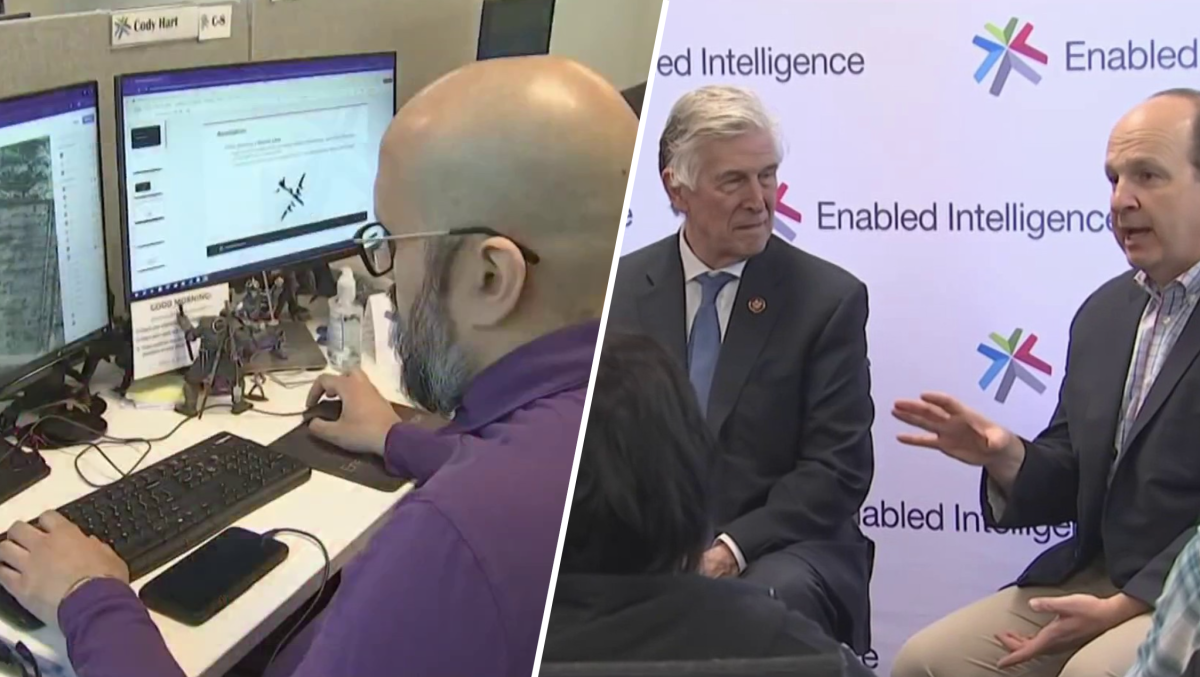

Local

Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia local news, events and information

"We were able to pick up the type of damage that we saw in the brain and now pick it up in the living animal and this is very helpful as we try to move this into the clinic to try to detect early fingerprints of the disease," Goldstein said.

Scans of the animals' brains showed leaky blood vessels and persistent changes in electrical functions, which could possibly explaining cognitive impairment in some people after similar injuries, BU Today reports.

“The same brain pathology that we observed in teenagers after head injury was also present in head-injured mice,” Goldstein told BU Today. “We were surprised that the brain pathology was unrelated to signs of concussion.”

Efforts to protect athletes have largely focused on preventing concussions, but the study suggests that head injuries that are not strong enough to cause a concussion can lead to CTE.

"The main message of this work is that concussion doesn't cause the CTE, but rather, the hit itself independent of concussion causes CTE," Goldstein said.

Although the study was small, Goldstein said studying even single cases of CTE can help researchers develop hypothesis to test.

Researchers said the key to reducing risk of CTE is reducing the number of head impacts to athletes and soldiers.