Editor’s Note: Go here for an update on the verdict in the victims’ families’ wrongful death lawsuit, and here for an exclusive interview with one victim’s parents.

What to Know

- Nina Brekelmans, 25, and Michael McLoughlin, 24, died a year ago after a fire broke out near Dupont Circle, on Riggs Place NW.

- D.C. officials found that the house where they rented rooms had not been inspected and was not licensed for rental.

- Cities across the country grapple with how to detect potentially dangerous illegal apartments, experts say.

The fire that sent flames shooting through the roof of a three-story rowhouse near Dupont Circle started on the first floor. An electrical short sparked in the landlord’s living room, and the blaze raced upward in the historic house.

We're making it easier for you to find stories that matter with our new newsletter — The 4Front. Sign up here and get news that is important for you to your inbox.

Four people were inside.

Nina Brekelmans awoke in the burning building and called 911, according to a lawsuit filed by her family. Firefighters arrived minutes later, but by the time they were able to reach her and her housemate Michael McLoughlin, it was too late.

Brekelmans, 25, and McLoughlin, 24, were killed by the blaze June 3, 2015 at 1610 Riggs Place NW, where they each rented rooms.

The housemates were trapped on the third floor of the house because there was no fire escape and the windows were painted shut, according to $10 million lawsuits their families each have filed against the father and son who owned and managed the building.

Local

Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia local news, events and information

In court filings, Len Salas and his father, Max Salas, each denied that negligence contributed to the deaths.

The alleged fire hazards in the house were not found by housing inspectors because the Salases rented out the units illegally, without verifying that the apartments met safety codes, according to the D.C. Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs, which administers housing inspections.

D.C. has a system to find and correct dangerous safety violations in apartments registered with the city. But illegal apartments often go unnoticed until a tragedy occurs.

In the District, the detection of potentially hazardous illegal apartments depends on renters to know their rights and neighbors to report anything suspicious, DCRA's director said. The same thing happens in cities across the country, experts say.

Since January 2013, the owners of at least 46 D.C. properties have been ticketed for operating housing without certificates of occupancy.

But D.C. officials believe the true number of illegal apartments is higher. If the owner of a property on the books as a single-family house rents out unsafe apartments or rooms, odds are slim that the illegal housing will be discovered, DCRA director Melinda Bolling said.

“We wouldn’t know,” she said. “We look to our [Advisory Neighborhood Commissions], citizens and the tenants themselves to be proactive to let us know about properties. We get information from those parties and we do compliance checks.”

The Smell of Smoke

When the fire broke out on Riggs Place, Brekelmans had just earned a master's degree from Georgetown University. She was preparing to fly to Jordan to research female runners, combining two passions of the Arabic speaker who ran every day, friends said. McLoughlin, who had degrees in finance and economics from the University of Maryland, was launching his career and had impressed his bosses at an insurance company with his energy and intellect, they told The Washington Post.

The housemates each paid about $1,500 a month for furnished rooms with separate kitchenettes, and a shared bathroom, the tenant who lived in the basement apartment of the house told the Post. He was out of town on business when the fire occurred.

Max Salas, 63, was in his bedroom on the second floor of the red brick rowhouse when he smelled smoke, he told fire investigators, according to a copy of the fire department’s incident report obtained by NBC Washington.

He opened his bedroom door and realized the smoke was coming from the first floor. He walked downstairs and saw the couch in his living room was on fire, and ran into the kitchen for a bucket of water, but the fire was spreading, the report says.

Salas ran back upstairs and tried to enter a second-floor bedroom where his grandson was sleeping, but the door was locked. He banged on the door until he was able to wake him and closed the door behind him, the report says.

He tried to go upstairs to the third floor to warn Brekelmans and McLoughlin, according to the report. But the flames and smoke were spreading too fast.

Salas and his grandson jumped through a second-floor window.

Brekelmans awoke and called 911 at about 2:30 a.m., the lawsuit filed by her family says. Firefighters arrived less than four minutes later, the fire department’s incident report says, but she and McLoughlin could not be saved.

They were pronounced dead at about 6:15 a.m., the lawsuits filed by the victims’ families say.

Salas, his grandson and three firefighters were injured but survived.

Investigators determined the fire started accidentally. In the wreckage of the Salas’ living room on the first floor, where the blaze was determined to have started, officials found an electrical plug with a damaged prong, an ungrounded two-prong extension cord and an oil-filled space heater, the investigation report says.

A month after the fire, DCRA fined Salas and his son $6,000 because they failed to obtain a license to rent rooms or apartments, which would have included proof of an inspection, the regulatory department said.

Brekelmans’ family’s lawyer, Patrick Regan, argued that if the house had been inspected, Brekelmans and McLoughlin would have been able to escape.

“The tragedy is, had the landlord gone through the required steps to get a permit, every single violation [alleged in the lawsuit] that led to the deaths of these two young people would have been caught,” he said. “These two young people would have been able to get out safely.”

The fire damage to the house was so extensive that inspectors were not able to determine if any code violations were present, DCRA spokesman Matt Orlins said.

“What we saw was a shell at that point,” he said.

In court filings, Max and Len Salas each denied that they failed to maintain the building or meet safety standards.

Len Salas’ lawyer, Michael Forster, said he could not comment on the circumstances of the fire and that Len Salas’ father, Max Salas, was responsible for the house.

“Max Salas took full responsibility in handling every aspect of acquiring licenses, maintaining and renting the property,” Forster said in an email.

To operate legally, the property needed an inspection and a certificate of occupancy for a two-unit rental property, DCRA found. The property did not have that inspection or license, according to the department.

Len Salas bought the house in 2007, according to D.C. property records and tax assessment records. Max Salas accepted rent checks, the basement tenant, John Mecham, told The Washington Post.

Max Salas’ lawyer did not respond to multiple inquiries.

Finding Illegal Apartments Is a ‘Cat and Mouse Game’

DCRA data shows property owners in nearly every corner of the District have operated apartments, rooming houses and bed-and-breakfasts without getting official confirmation that conditions are safe.

D.C. apartments are inspected on three occasions: when a property owner applies for a license to rent, when DCRA workers perform periodic inspections of legal apartments and when inspections are requested.

But when property owners rent illegally, the apartments aren’t checked, Bolling, the DCRA director, said.

“When a property doesn’t have a license and we’re not told about it, that’s where problems can arise,” she said.

Some illegal apartments are found by DCRA’s housing investigations unit, whose techniques include inspecting properties after seeing suspicious Craigslist ads. But, most units without certificates of occupancy are found after DCRA receives a tip from a tenant or neighbor who suspects something is not right, Orlins, the department’s spokesman, said.

In cities across the country, illegal apartments often are not found until it’s too late, said Robert Neale, a vice president of the International Code Council, which publishes safety codes adopted by states and government agencies nationwide.

“Typically local fire services don’t do any inspection of single-family homes or duplexes,” he said. “They typically only find illegal apartments when there’s a tragedy.”

Privacy concerns block inspectors from checking every single-family home for hazards, said Robert Solomon, a manager at the National Fire Protection Association, which also sets safety standards.

“It’s the ‘man’s home is his castle’ provision,” he said.

Finding illegal apartments vexes many fire departments and city governments, Solomon said.

“It really is like a cat-and-mouse game,” he said.

In 2015, DCRA inspected 21,004 housing units. The majority of the homes, 47%, were inspected as part of the periodic, proactive inspection program, which requires that every five years a percentage of the units in a multi-unit building is inspected, depending on the total number of units.

About a third of total inspections last year were complaint-based, and about 12 percent occurred because the property owner applied for a license.

Infractions were found in 644 units — about 3 percent.

If a violation, such as insufficient exits, poses an immediate danger to residents, a property owner is ordered to correct the issue right away, Orlins said. If the owner fails to do so, DCRA can shut down the building, fix the problem and bill the owner for the cost.

When illegal apartments are found, DCRA often opts to work with property owners to bring the units into compliance with the law, Bolling said.

“What we're trying to do is maintain, preserve and increase affordable housing,” she said. “When we find someone who is operating outside of the law, we work to bring them inside, versus [shutting] it down ... We can work with you."

Fines for operating housing without proper permits may be waived. But, existing infractions will stand, Orlins said.

Renters often are not aware of what they are entitled to, and in a tight rental market they can find themselves forced to accept homes that are illegal or hazardous, said Beth Mellen Harrison, a supervising attorney in the Legal Aid Society's housing unit.

“There may be properties where tenants accept quite dangerous conditions because they don’t have anywhere else to go,” she said.

About half of the approximately 500 housing cases the Legal Aid Society handles in D.C. every year for low-income clients involve homes with unsafe exits, such as basement apartments with windows too small for a person to crawl out of if a fire breaks out.

In one case, a resident’s front door could only be unlocked from the outside.

“They had to call somebody to get them out,” Harrison said.

ANC commissioner Michael Upright, who represents the leafy neighborhood where the Riggs Place fire occurred, said he worries there are unsafe and illegal apartments in the area.

“I do feel there are others out there just like this that we just don't know about,” he said.

‘We Don’t Want Anybody Else to Die’

After the deadly fire on Riggs Place, Georgetown University – where Brekelmans earned her master’s degree – handed over students’ off-campus addresses to DCRA inspectors, Bolling said. On Aug. 15, 2015, inspectors performed safety checks on student apartments.

DCRA initiates many inspections, but one of the regulatory department’s most important roles is to educate renters about when they should ask for inspections themselves, the director said. DCRA regularly meets with universities and social service organizations to help inform residents of their rights, Bolling said.

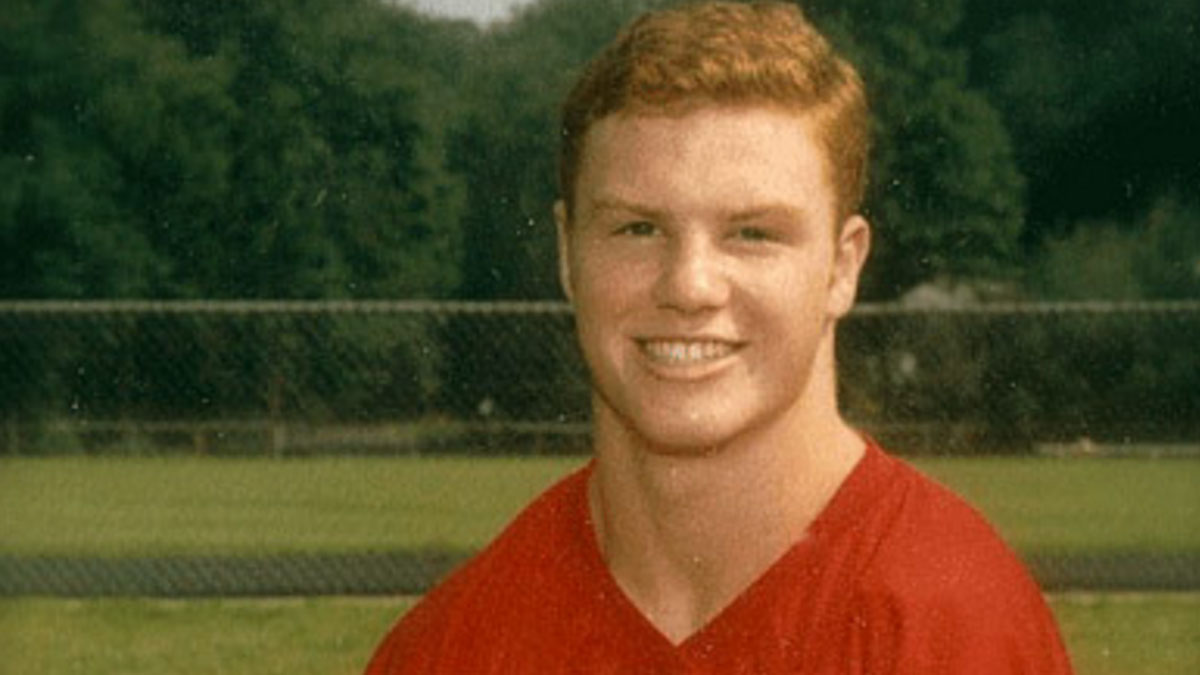

Georgetown graduate Jay Tedino has taken educating renters about safety into his own hands. After his friend was killed in a fire, the 33-year-old has spent the past decade trying to prevent young people from dying in rental properties they did not realize were dangerous.

Tedino felt a familiar pain when he heard about Brekelmans’ and McLoughlin’s deaths. His friend Daniel Rigby died in a house fire in 2004, days before he would have turned 22.

Rigby died Oct. 17, 2004 when a fire broke out at 3318 Prospect St., a block north of busy M Street. He would have graduated with the Georgetown class of 2005.

Inspectors later found metal bars welded to the window frames, a lack of required smoke detectors and blocked exit doors, according to news reports.

Two years after Rigby died, Tedino helped found Friends of Rigby, a nonprofit organization that educates college students about fire hazards and raises more than $10,000 per year to pass out smoke detectors, fire extinguishers and more.

As Rigby enjoyed his senior year in college, he likely didn't consider whether the house he shared with five roommates was safe, Tedino said.

"We were at the age when you think you're invincible," he said.

The night before the fire, Rigby and Tedino, who went to high school together in New Jersey, watched the New York Yankees advance in the playoffs. They celebrated a 19-8 win against the Boston Red Sox until about midnight, and then Tedino went to sleep in his house down the block.

Tedino awoke to pounding on his door.

"There's a fire at 3318 and Danny's MIA," Tedino’s friends told him.

Hours later, Rigby was confirmed to have died in the basement of his house.

On a bitterly cold Saturday morning in April, Tedino and about 20 Georgetown students walked in the rain to off-campus student apartments. Teams of volunteers knocked on the doors of houses where they said students can expect to pay about $1,500 per room. They rattled off 15 questions on a safety survey.

Armed with iPads, they asked students how many smoke detectors and fire extinguishers they had, when the devices were last tested, whether any extension cords were used and if they knew when DCRA last performed inspections. If the students needed any equipment, Friends of Rigby passed it out.

As Tedino walked door to door, he told students the supplies were free but asked them to "pay it forward" by participating in the group's annual gala and 5K race.

After hours on the streets, Friends of Rigby had spoken with residents of 370 properties and handed out 40 smoke and carbon dioxide detectors.

If Friends of Rigby can get just 10% of the students that volunteers speak with to improve the safety of their homes, the group will be a success, Tedino said.

"We don't want anybody else to die," he said.

The group is working with the Red Cross now to set dates to go door-to-door in D.C. and New Jersey this fall, when college students move in to new apartments.

Carrying a stack of smoke detectors as he surveyed the historic rowhouses of Prospect Street, Tedino was struck by the difference between the neat exteriors of the million-dollar homes and the fire hazards he knew might lurk inside.

"They look OK from the outside, but it's what's inside that's scary," he said.