Its doors and windows shuttered and its paint peeling, the old cottage rests on steel and wooden beams in a parking lot behind Main Street Station. The Richmond Slave Trail runs right past it; next door is the site of the notorious Lumpkin’s Slave Jail. Traffic from Interstate 95 roars behind it, a few feet away.

If you didn’t know any better, you might think the cottage has merely been temporarily deposited here, waiting for a truck to return, lift it onto its bed and carry it to a new home. In reality, the cottage has had no permanent address for 20 years, and has spent most of the past decade here, hidden in plain sight.

It represented yet another untold story about African Americans in Richmond.

Jan Meck, author, "The Life & Legacy of Enslaved Virginian Emily Winfree"

Though neglected and in limbo, the significance of the weather-beaten building is not unrecognized. A sign posted in front announces it as Winfree Cottage, the 19th-century home of Emily Winfree, a once-enslaved woman who after the Civil War raised her children — some of whom were fathered by her one-time owner — in the modest, two-room dwelling when it stood across the river in Manchester.

We're making it easier for you to find stories that matter with our new newsletter — The 4Front. Sign up here and get news that is important for you to your inbox.

A few years ago, before the sign arrived, the dilapidated cottage spoke to Jan Meck, not just in terms of the history it told, but of the history it didn’t.

“It represented yet another untold story about African Americans in Richmond,” says Meck, who became acquainted with the cottage while on a journey of personal discovery, seeking local history that she felt had been kept from her growing up.

She saw the cottage for the first time while on a tour sponsored by The Valentine museum for local tour guides. Suitably intrigued, she began to dig deeper to learn more about Emily Winfree.

She eventually partnered with genealogist Virginia Refo, documented details about Winfree and proceeded to do something that she — a white, retired NASA pharmacologist — could scarcely have imagined a few years ago: She wrote a book about the complicated, difficult life of a Black woman who was enslaved and then emancipated and managed despite all of the sufferings and the odds stacked against her to make a life for herself and her children, which resonates generations later through her descendants.

It’s a story about the horrors of slavery, the resilience of Winfree and the importance of preserving her home as a piece of history. Meck hopes her book, “The Life & Legacy of Enslaved Virginian Emily Winfree,” will raise awareness and funding to find a permanent home for the cottage. But the book is something much more, says Winfree’s great-great-granddaughter Emily J. Jones.

“It’s not about just another hardship story because that should be something that most Americans understand about that time, but what it looks like in these generations that have gone on from Emily,” said Jones, director of the New York State Education Department’s Technical Assistance Partnership for Equity at Bank Street College of Education. “Because I think that’s what Emily would want us to share.

“She would want to say, ‘Yes, this is what my life was’ ... but then, ‘This is what it looks like when you do what I did, when you pushed the way I pushed and you survived the way I survived’ and then all of these children have these gazillion lives.

“That’s important, and I think that’s what brings us to a more comprehensive conversation around American history. Also it brings us as humans closer because there’s something in Emily’s story that a white Trump supporter, even if they don’t want to admit it, could relate to.”

I became more and more outraged at the lies I had been told in school and by my parents. It became my passion to learn as much as I could about the true history of African Americans in my town of Richmond.

From the preface of Jan Meck's "The Life & Legacy of Enslaved Virginian Emily Winfree"

Meck, 73, grew up in Northern Virginia in the white suburbs of Washington, D.C., and the nation’s capital is the only place she ever saw anyone of color. She was accustomed to hearing disparaging remarks about Blacks, and the history she learned in school has long since been exposed for being one-sided and distorted.

It wasn’t until she went to college in Michigan that she began to “learn some truths,” she writes, and not until after she retired from NASA, returned to Richmond in 2011 and volunteered as a docent at the Virginia Historical Society (now the Virginia Museum of History & Culture), particularly its “Story of Virginia” gallery, that she began to understand how incomplete her education had been.

“I became more and more outraged at the lies I had been told in school and by my parents. It became my passion to learn as much as I could about the true history of African Americans in my town of Richmond,” she writes in the book’s preface.

She learned enough to develop her own driving tour, “African-American Heroes of Richmond,” and offered it free to anyone. One Saturday soon after he arrived in Richmond, Jamie O. Bosket, president and CEO of the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, rode along.

"Someone Has Got to Do This Research"

“We spent a good two or three hours driving around Richmond, which was a welcome opportunity to see the city, but particularly to hear some of these stories that she brought forward with such passion,” Bosket recalled. “She was so invested in it.”

When they arrived at the cottage, Bosket was intrigued by the story he didn’t know and started asking questions about Emily Winfree that Meck could not answer.

“I just turned to Jan,” recalled Bosket, “and said — I can still remember the moment — ‘Someone has got do this research. There must be something somewhere that would speak to Emily’s story.’”

Meck accepted the challenge and began doing the sort of research she had never done before — some of it at the VMHC. Bit by bit, she started piecing together Winfree’s story, which only made her want to find out more.

“It was life-changing,” she said.

Bringing in genealogist Refo “really took it to the next level,” Meck said.

They went looking for original documents and materials and, though such records of the enslaved are difficult if not impossible to find, were able to chronicle much of Winfree’s life and six generations of her family.

Through census data, court records, physician’s reports and other sources, Meck and Refo constructed a framework of Winfree’s life through its milestones: when she and her daughter were sold for $1,025 in 1858, the places she lived in enslavement, the children she birthed, the domestic jobs she held after emancipation, and her 33-year, part-time employment at Masonic Manchester Lodge #14 as a cook.

In regard to the cottage, they found the 1866 deed showing it was given to her by David C. Winfree, a white Chesterfield County landowner who became her owner just before the Civil War. There is evidence to suggest he was also the father of some of her seven children. In addition to the cottage, he gave her a 109-acre tract of his Chesterfield land. David Winfree died in 1867.

Beyond the official accounts, their relationship is unclear. It was not unusual for white owners to rape enslaved women as a way to increase their wealth by way of more enslaved offspring. Providing homes and property to the women after emancipation might not have been as typical.

There is no record of David Winfree, nor Emily Winfree, ever being married. Emily Winfree used his last name and was known, even to at least some in his family, as “Mrs. Winfree.” She was listed as “widow” on her death certificate in 1919.

Tracing Emily Winfree's Family Tree: A Powerful But Complicated Legacy

In addition to the documented evidence about Emily Winfree, Meck and Refo delved further into her story by tracing her family tree and finding dozens of living descendants, including Emily Grace Jones Jefferson, now in her 90s, who grew up in Richmond, attended Armstrong High and Virginia Union University and now lives in Maryland; others, such as great-great-granddaughter Jones grew up farther afield, their ancestors having left the South during the migration of Black people to other parts of the country.

Meck makes the point that the resilience and fortitude of Emily Winfree, who was denied an education and for so many years her freedom, is reflected in the achievements of her descendants, which include teachers, community leaders, successful business owners, a military officer and several with doctoral degrees in science, education and engineering.

“There was an expectation around the name,” said Jones, who, like others in previous generations, were given the name of Emily in honor of her great-great-grandmother. “I did not understand it when I was growing up, but I do now. There was an expectation to be focused, be a little more serious. That kind of ethic and almost like personal culture. You have a big name.”

It’s a powerful legacy but a complicated one, Jones said, because of David Winfree. Through the generations, lighter-skinned members of the family went on to marry white men and women and “moved on to a white world,” she said, some reluctant to even acknowledge those left behind.

As a result, also built into the expectations surrounding the name of Emily was the need to show “‘the blacker side’ of the family was just as accomplished or just as amazing, not in some sort of showy way,” Jones said. “It wasn’t about that. It was about who you really are, what your character is.

“Because of how much of a hit it is for Black folks to have family that passes (for white). That’s such a gut hit. That’s what we were trying to address by way of academic and professional success, not so much that we have these degrees ... but more like, there’s a secret thing we have to address in this family and the way we do that is by showing up and being a person who ... embodies everything that your cousins may have been thinking they needed to get away from.”

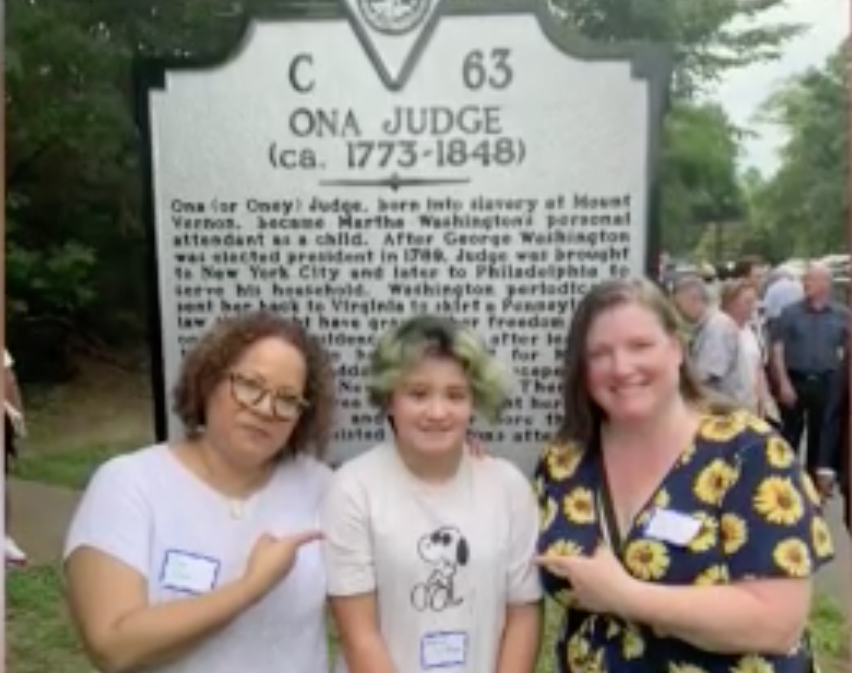

In July 2018, the Virginia Museum of History & Culture invited descendants to gather in Richmond for a presentation by Meck and Refo and a tour of the sites related to Emily Winfree. Another reunion is scheduled for this coming June at the museum.

Saving Emily Winfree's Cottage

Emily Winfree’s name was not widely known until 2002 when her cottage was slated for demolition and preservationists stepped in. ACORN, the Alliance to Conserve Old Richmond Neighborhoods, moved to save the cottage, saying it was historically significant as representing a part of post-Civil War Richmond where Blacks lived and worked.

The cottage was donated to the city and moved out of harm’s way. ACORN worked with the city to develop a plan to restore the cottage and find a permanent home for it and even raised money for such a project but, in the end, the efforts became mired within the city’s bureaucracy, Meck reports, and nothing came of it. The money was returned to donors.

The cottage, though it underwent modest repairs a few years ago, still sits forlornly at its “temporary” location, but at least Emily Winfree’s story is becoming known. Her story “represents so many others that we don’t have the materials that we do for Emily,” said VMHC’s Bosket.

“And I think when you look at it on the whole, you turn back and say, ’My gosh, what a shame that cottage remains there after (so many years),” he said. “It had a little love given to it, but certainly not enough for the story that it represents.”

As for the cottage, the interpretative sign was added in 2019 because there was so much confusion surrounding it, said Kimberly M. Chen, senior manager in the city’s office of the deputy chief administrative officer for economic development and planning.

A more permanent solution for the cottage “needs to be found,” Chen said in an email.

“The city is open to proposals or suggestions,” she wrote.